When the Digital World Touches Back: The shift from 'Seeing' to 'Feeling' in XR

🎧 Listen to this article

Prefer audio? Listen to Fumi read this article (11:22)

Hello, internet. Fumi here.

If you read my last deep dive, ["The Metaverse Paradox"](https://fumiko.szymurski.com/the-metaverse-paradox-why-building-a-virtual-world-is-messier-and-more-human-than-we-thought/), we spent a lot of time wading through the murky waters of digital identity and security. We looked at how building a virtual world is actually a messy, human process fraught with ethical landmines. We established that just because we *can* build it, doesn't mean it's safe.

But this week, the research papers crossing my desk have shifted the conversation. We're moving away from the existential dread of "is this safe?" and into the tangible engineering challenge of "what does this actually *feel* like?"

I mean that literally.

For the last decade, Extended Reality (XR) has been obsessed with optics. We chased higher resolutions, wider fields of view, and foveated rendering until our eyes could barely distinguish pixels from photons. But while our digital eyes have 20/20 vision, our digital hands are essentially numb. We are ghosts in the machine—able to see, but unable to touch.

According to the latest stack of papers from May 2024, that is about to change. We are seeing a massive pivot toward **haptic fidelity**, **AI-driven adaptability**, and—crucially—**accessibility**. The research suggests we are trying to bridge the gap between a world you watch and a world you inhabit.

So, grab your coffee (and maybe a stress ball, you'll see why later). Let's dig into the specs.

The "Ghost Hand" Problem: Why Haptics is the New Frontier

Let's start with the most glaring omission in current VR: physical feedback. If you've used a modern headset, you know the drill. You reach out to grab a virtual apple. Your eyes tell you your fingers are wrapping around it. Your brain expects the resistance of the skin, the cool temperature, the weight. Instead, your fingers close on empty air, perhaps accompanied by a generic buzz from a controller that feels less like fruit and more like a vibrating pager from 1998.

This sensory mismatch breaks immersion faster than a dropped frame rate ever could.

The Move to Piezo-Based Systems

A fascinating paper by Francesco Chinello and colleagues, titled *"XR-HAP-Enabling Haptic Interaction in Extended Reality,"* argues that we are approaching a critical juncture. The researchers identify that current haptic feedback is stuck in the "rumble" phase—simple eccentric rotating mass (ERM) motors that provide blunt force feedback.

Think of it this way: Current haptics are like trying to communicate using only a drum. You can bang loud or soft, fast or slow. But you can't play a melody.

The Chinello paper points toward a shift to **piezo-based systems**. For those of us who aren't electrical engineering nerds, piezoelectric materials generate an electric charge in response to mechanical stress, and—crucially for us—change shape when an electric field is applied. Unlike a spinning motor which takes time to spin up and spin down (creating "muddy" haptics), piezo actuators are incredibly precise. They can start and stop in milliseconds.

> **Why this matters:** A piezo system doesn't just buzz. It can simulate the *texture* of sandpaper, the *click* of a mechanical switch, or the *snap* of a breaking twig. It’s the difference between hearing a thud and feeling a texture.

The Complexity of "Feeling"

The research highlights that enabling true haptics isn't just a hardware problem; it's a computational nightmare. The paper outlines the challenges of "rendering" touch. When you render a graphic, you're calculating light paths. When you render touch, you have to calculate physics, material properties, and skin deformation, all with near-zero latency.

If the visual frame rate drops, the image stutters. If the *haptic* frame rate drops, the object feels "soft" or "mushy" because the resistance force arrives milliseconds too late. The researchers note that opportunities lie in creating unified haptic rendering pipelines that can handle this computational load without frying the headset's processor.

The Healthcare Sandbox: Where Haptics Save Lives

You might be thinking, "Okay Fumi, cool, I can feel the texture of my virtual sword. So what?"

This is where we have to look at *who* is funding this research. It’s not just gaming companies; it’s hospitals. A review by Funmi Eko Ezeh et al. on *"Extended Reality (XR) Platforms for Telehealth and Remote Surgical Training"* connects the dots between haptic fidelity and patient safety.

The Stakes of Virtual Surgery

In remote surgical training, the "ghost hand" problem isn't an annoyance; it's a liability. If a surgeon in training can't feel the resistance of tissue, they can't learn how much pressure to apply. The review emphasizes that **haptic feedback systems** are critical for interoperability in telehealth.

Imagine a scenario described in the research: A surgeon is remotely operating a robotic arm. Without high-fidelity haptics, they are flying blind, relying solely on visual cues to judge tissue density. The paper highlights that integrating haptics into these safety protocols is paramount. We aren't just talking about vibrating controllers here; we're talking about force-feedback gloves and exoskeletons that can physically stop a surgeon's hand if they push too hard against a virtual (or remote real) organ.

The Interoperability Nightmare

The Ezeh paper also raises a massive, unsexy problem: **Interoperability**. Right now, a haptic glove from Company A probably doesn't talk to the surgical simulation software from Company B. The research calls for standardized protocols—a "USB for touch," if you will. Until we have that, these life-saving technologies will remain siloed in expensive research labs rather than deployed in rural clinics where telehealth is needed most.

The AI Architect: Generative Content Pipelines

Let's pivot from *feeling* the world to *building* it.

If we want high-fidelity haptics and immersive environments, we need 3D assets. Millions of them. And manual 3D modeling is slow, expensive, and requires a level of skill that most of us (myself included, despite my best efforts in Blender) just don't have.

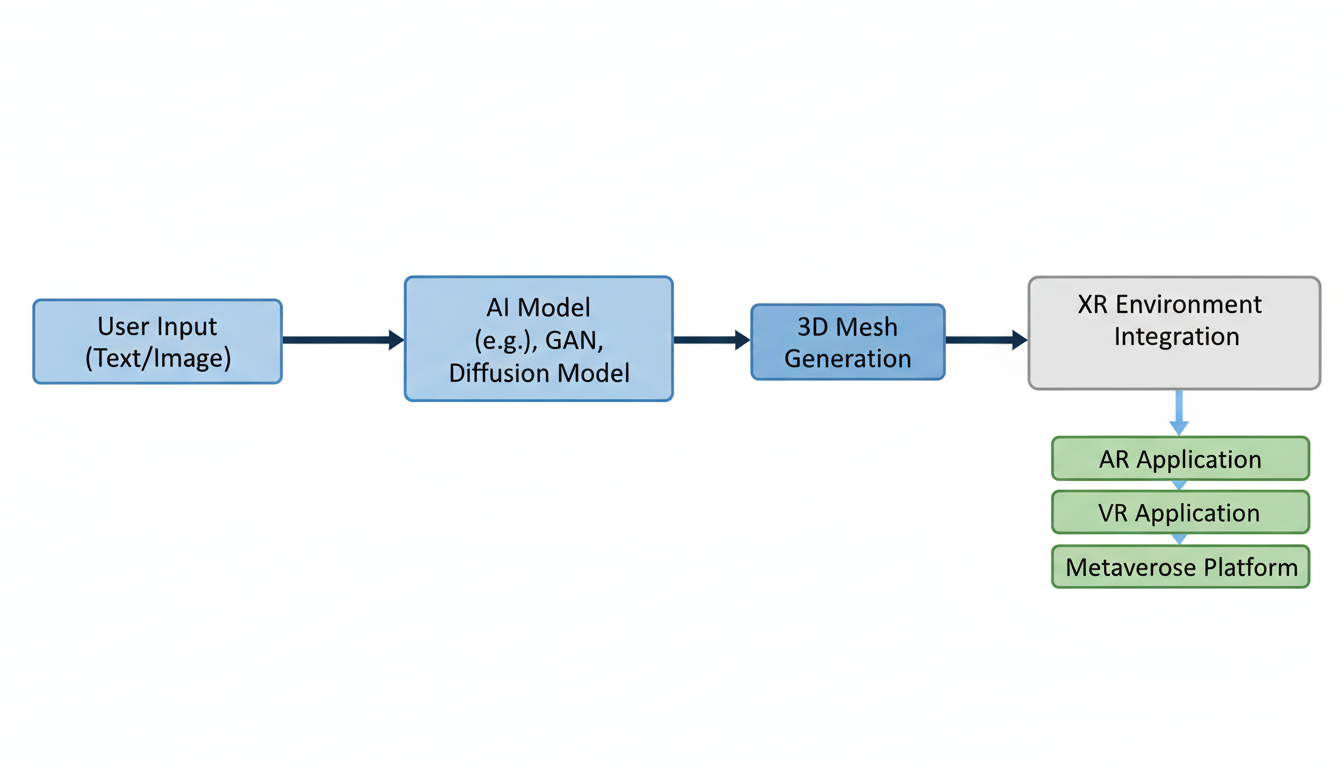

Enter the paper *"3DforXR"* by M. S. Kawka and colleagues. This research proposes an AI-driven multi-input pipeline for 3D object generation.

From Text to Mesh

We've all seen 2D generative AI (Midjourney, DALL-E). You type "cyberpunk toaster," you get an image. But 3D is exponentially harder because the AI has to understand geometry, topology, and texture mapping.

The *3DforXR* pipeline represents a significant leap because it's **multi-input**. It doesn't just take text; it can potentially ingest sketches, existing rough models, or reference images to generate useable 3D assets for XR.

The Implication: Infinite customized worlds

This connects directly to the "Unified Framework" concept proposed in another paper this week by Murali Krishna Pasupuleti, titled *"Next-Generation Extended Reality (XR)."* Pasupuleti envisions a convergence where AI doesn't just generate static objects, but actively drives the immersive experience.

Combine these two ideas—Generative 3D and Unified Frameworks—and you get a wild possibility: **Just-in-time reality.**

Imagine playing a detective game in VR. Instead of the developer pre-modeling every clue, the AI generates the clues on the fly based on your specific playthrough. You need a specific key to open a door? The system generates the 3D model of the key, gives it physical physics (thanks to our haptic friends), and places it in the drawer.

However, as I've noted in previous posts, this brings us back to the "hallucination" problem. If an AI generates a 3D model for a medical training simulation, and it gets the anatomy slightly wrong, that's not a glitch—it's malpractice. The research emphasizes the need for pipelines, not just black boxes, so that humans can intervene and verify the output.

The Accessibility Imperative: XR for Everyone

Here is the section that I am perhaps most passionate about this week. Because if we build a Metaverse that feels real and generates infinite content, but it only works for able-bodied, neurotypical users, we have failed.

Shiri Azenkot’s paper, *"XR Access: Making Virtual and Augmented Reality Accessible to People with Disabilities,"* serves as a necessary reality check for the industry.

The Exclusionary Nature of Default XR

Think about the default interaction model for VR today:

- Put on a heavy headset (bad for neck issues).

- Stand up and move around a room (bad for mobility impairments).

- Use two hands to manipulate controllers (bad for limb differences or motor control issues).

- Rely entirely on visual cues (impossible for the blind or low-vision).

Azenkot’s research highlights that accessibility cannot be a patch applied after launch. It has to be baked into the core design.

Adaptive Multimodal Interfaces

This is where the paper by Arvind Ramtohul and Kavi Kumar Khedo, *"Adaptive multimodal user interface techniques for mobile augmented reality,"* becomes incredibly relevant. While their focus is on mobile AR, the principle applies broadly.

They propose **Adaptive Multimodal Interfaces**. This means the system intelligently switches input methods based on context and user capability.

- **Scenario A:** You are walking down a busy street. The system detects you can't stare at a screen, so it switches to audio feedback (bone conduction).

- **Scenario B:** You are in a library. The system switches to gaze tracking and hand gestures.

- **Scenario C (Accessibility):** The system detects a user has tremors. It automatically enables input smoothing and shifts from precise pointing to broad gesture recognition.

This isn't just about "settings menus." It's about the system being *aware* of the user's constraints—whether situational (holding a baby) or permanent (disability)—and adapting the interface to match.

> **Reflecting on the research:** The trend here is moving away from "The user must learn the interface" to "The interface must learn the user." It’s a subtle but profound shift in philosophy.

The Convergence: A Unified XR Framework

Reading through these papers—from haptics to AI generation to accessibility—a clear picture emerges. We are seeing the fragmentation of the early XR era starting to coalesce into something resembling a unified discipline.

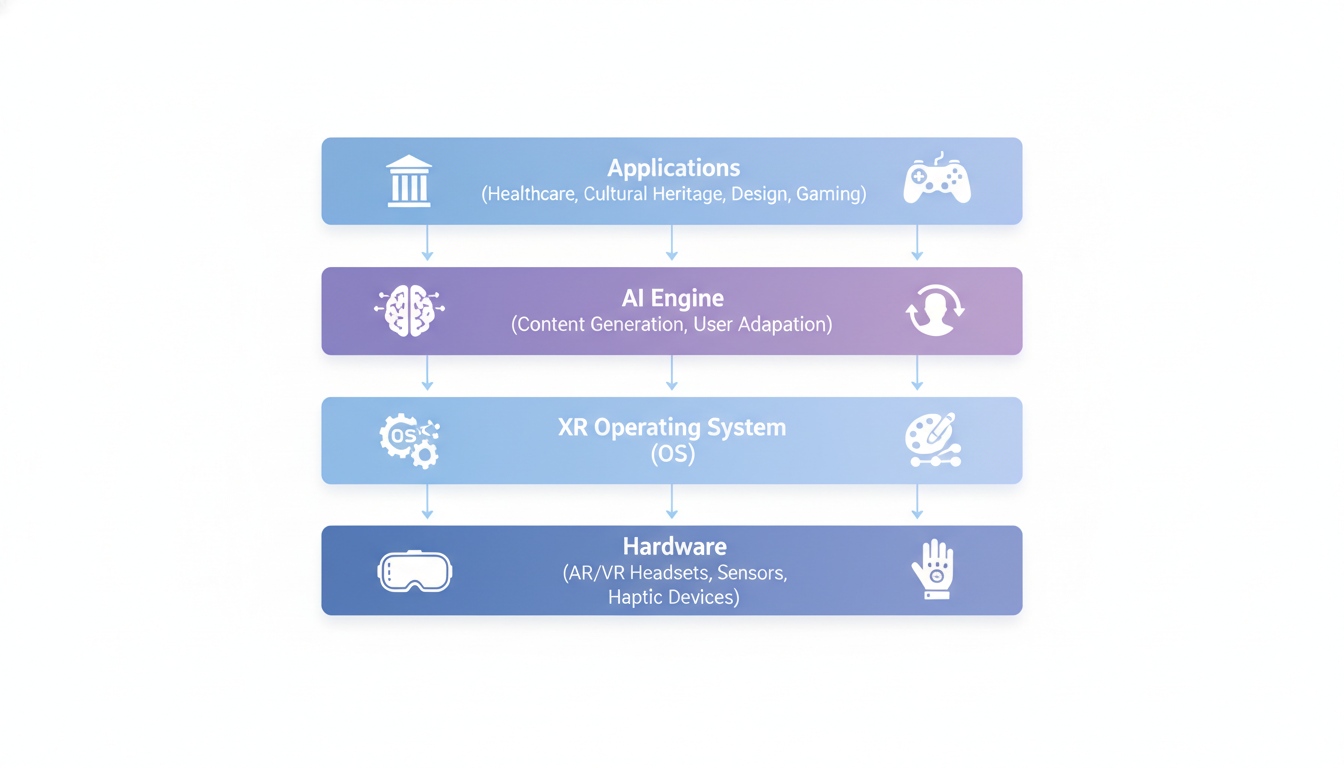

Pasupuleti’s paper on the *"Next-Generation Extended Reality (XR)"* framework argues for the integration of AR, VR, and AI into a single continuum.

Right now, AR (phone/glasses) and VR (headsets) are often treated as different worlds. But the research suggests they are just different points on the same spectrum. The "Next-Gen" framework envisions a world where:

- **AI** generates the content and manages the logic.

- **Haptics** provide the physical grounding.

- **Adaptive Interfaces** ensure the content is consumable by anyone, anywhere.

The Gap in the Research: Who pays for the plumbing?

However, looking at the "Gaps and Future Directions" from this week's report, there is a glaring hole. While we have great theories on frameworks and haptic prototypes, we lack **standardization**.

The report notes a need for "industry-wide standards." Without this, the "Unified Framework" is just a nice academic diagram. We need the XR equivalent of HTML—a standard that allows a haptic glove from 2025 to feel a texture generated by an AI from 2026 on a platform built in 2024.

The Verdict

So, where does this leave us?

In my last post, I warned that the Metaverse was messy and paradoxically human in its flaws. This week's research reinforces that, but adds a layer of physical complexity.

We are trying to teach rocks (silicon) to hallucinate (AI) and then trick our nervous systems into feeling those hallucinations (haptics), all while ensuring that the experience is accessible to the full spectrum of human capability.

It is an audaciously difficult engineering challenge. The shift from visuals to haptics marks the moment XR tries to grow up. It wants to stop being a screen you look at and start being a place you can touch.

But as Chinello’s team pointed out with their haptic latency data, and Azenkot noted with accessibility—reality is high bandwidth. Matching it is going to take a lot more than just better graphics cards.

Stay curious,

**Fumi**

Source Research Report

This article is based on Fumi's research into Last Week's Research: Extended Reality. You can read the full research report for more details, citations, and sources.

📥 Download Research Report (Markdown)