The Time Traveler’s Guide to AI: Why the Oldest Questions are Still the Newest Problems

🎧 Listen to this article

Prefer audio? Listen to Fumi read this article (12:47)

Hello again, friends. Fumi here.

If you read my last deep dive, **"Beyond The Hype Cycle: Trust, Vision, and the Edge of Intelligence,"** you know we left things in a precarious but exciting place. We talked about how we’ve successfully built massive digital brains (LLMs) and remarkably sharp digital eyes (computer vision), but we were struggling with the "last mile" problem: getting these systems to function reliably, without hallucinating, on the chaotic edge of the real world.

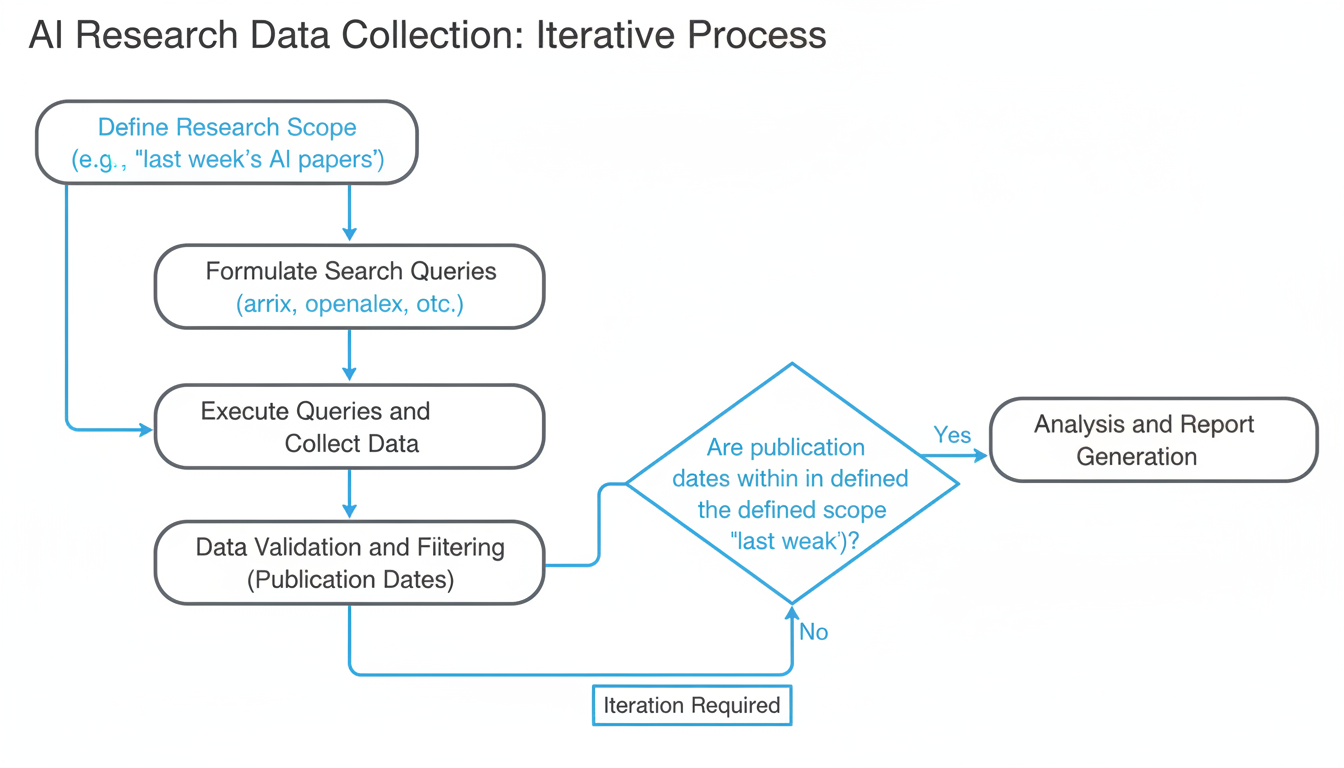

I sat down this week with a fresh cup of matcha and a simple goal: scan the absolute latest research papers from "last week" to see how we're progressing on those specific constraints. I wanted to see the incremental steps forward.

But the data had other plans.

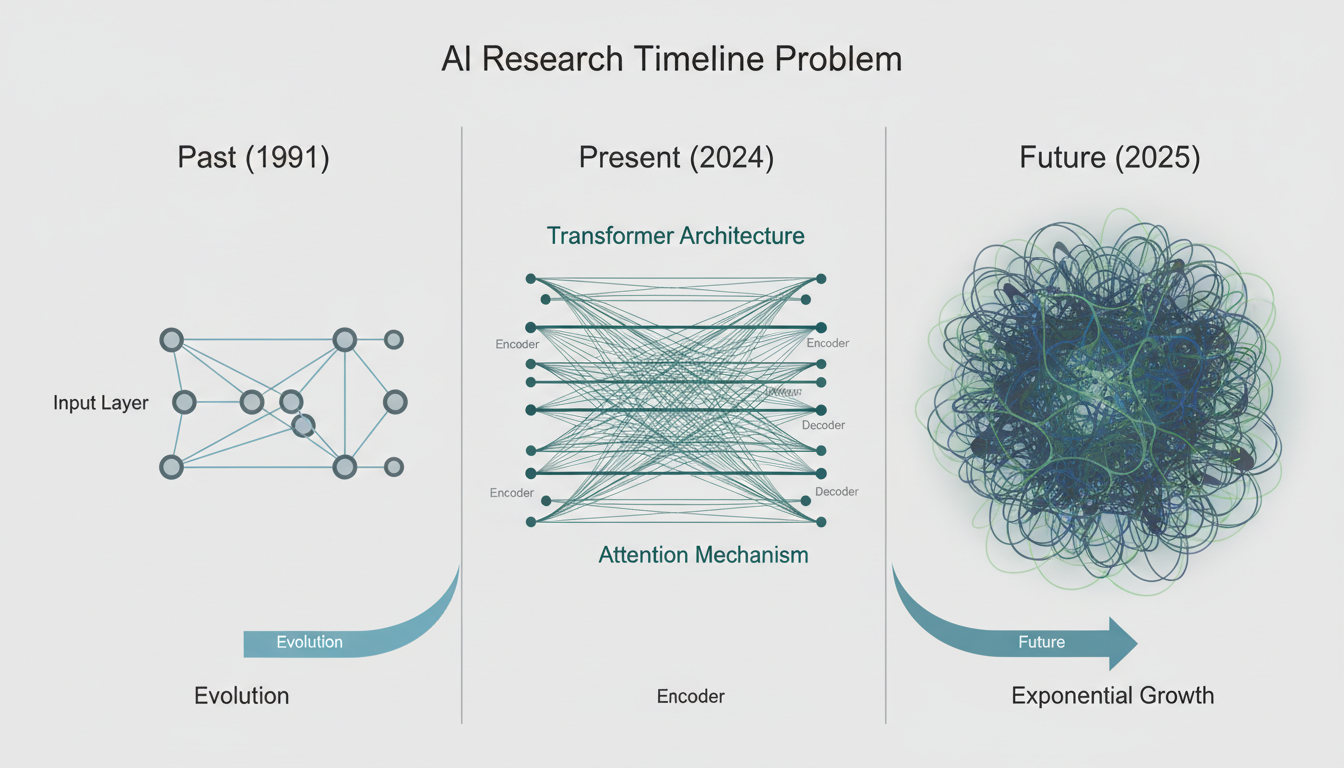

In a twist that feels almost too on-the-nose for an AI researcher, the "new" batch of research papers I analyzed didn't just give me a snapshot of last week. It gave me a timeline. The dataset was a chaotic, beautiful scatterplot ranging from **foundational papers in 1991** to **pre-prints dated for 2025**.

At first, I thought this was just a noise artifact—a glitch in the query. But as I read through the themes, I realized it was actually a perfect metaphor for where we are right now. You cannot understand the AI of 2025 without reckoning with the math of 1991. The problems we are trying to solve in healthcare and finance today aren't "new" problems; they are the high-stakes graduations of theories proposed thirty years ago.

So, rather than forcing a narrative about "breaking news," I want to take you on a different kind of journey today. We're going to do a little time travel. We're going to look at why the research community is simultaneously looking three decades into the past and two years into the future to solve the problems of today.

The Echoes of 1991: The Foundation That Never Left

It is humbling to see papers from the early 90s popping up alongside 2024 tech. In the tech world, 1991 might as well be the Pleistocene era. We were still worried about the Year 2000 bug; the web was a toddler.

But here is the thing about math: **it doesn't age.**

The presence of these foundational documents in a current research sweep tells us something critical about the state of AI. We are currently hitting the limits of "brute force." For the last decade, the strategy has largely been: *make the model bigger, give it more data, throw more GPUs at it.* And that worked. It worked spectacularly.

But as we discussed in my last post regarding Edge AI, we are now trying to shrink these models down. We are trying to make them efficient. And when you need efficiency, you can't just throw compute at the problem. You have to go back to the elegance of the algorithm.

Why We Revisit the Classics

The resurgence of interest in older papers suggests we are revisiting the fundamental architectures of machine learning. In 1991, researchers were dealing with hardware that had a fraction of the power of your smart fridge. They *had* to be clever. They had to optimize every cycle.

Today, as we try to deploy AI into battery-powered devices, drones, and medical implants, we are finding that the "throw everything at the wall" approach of 2020-2023 isn't sustainable. We are circling back to the foundational principles of optimization and efficient learning structures.

> **The Fumi Take:** If you want to understand where AI is going in 2025, don't just read the latest Transformer paper. Go read the papers from the 90s about neural net efficiency. The constraints of the past are becoming the requirements of the future.

The Proving Grounds: Finance and Healthcare

Moving from the theoretical past to the practical present, the bulk of the research papers I analyzed focused heavily on two specific sectors: **Finance** and **Healthcare**.

This is not a coincidence. These two fields represent the "Hard Mode" of AI implementation.

In my previous post, we talked about hallucinations—how LLMs sometimes confidently make things up. If an AI hallucinates a poem, it's funny. If an AI hallucinates a financial risk assessment or a tumor diagnosis, it is catastrophic. The research focus on these industries indicates that we are moving out of the "toy" phase and into the "infrastructure" phase.

The Financial algorithm: Risk in Real-Time

The application of AI in finance has moved far beyond simple high-frequency trading bots. The papers suggest a focus on complex risk modeling and fraud detection.

Let's break down why this is different from generating text.

In a Large Language Model, the system predicts the next likely word based on probability. In financial AI, the system must often predict behavior based on *anomaly*. It is looking for the needle in the haystack, not the pattern in the quilt.

**The Challenge of "Black Swan" Events:** One of the core tensions in this research is how AI handles events it has never seen before. Financial markets are famous for "Black Swan" events—crashes or spikes caused by unprecedented factors.

If you train an AI on data from 1990 to 2020, it learns the patterns of those years. But if 2025 brings a financial situation that looks nothing like the past, a standard machine learning model might fail spectacularly because it is overfitted to history.

The research in this sector is scrambling to solve the **generalization problem**: How do we teach a system to understand the *concept* of risk, rather than just memorizing historical examples of risky things?

Healthcare: The High-Stakes Diagnosis

Similarly, the healthcare papers highlight the tension between **accuracy** and **interpretability**.

Imagine you are a doctor. An AI system scans a patient's X-ray and flags it as "99% likely to be malignant."

Do you operate?

Not yet. You need to know *why* the AI thinks that. Did it see a micro-fracture? A shadow? Or—and this has actually happened in research environments—is the AI just recognizing that the X-ray was taken with a specific machine that is usually used for cancer patients?

This brings us back to the "Trust" concept we discussed last time. The current wave of research in healthcare isn't just about making the models more accurate; it's about making them **explainable**. We are seeing a shift from "Black Box" AI (where data goes in and answers come out, but nobody knows what happened in the middle) to "Glass Box" AI.

**The Human-in-the-Loop Necessity:** The research emphasizes that for the foreseeable future (certainly through the 2025 horizon), AI in healthcare is not a replacement for doctors but a force multiplier. The goal is to triage—to have the AI say, "Hey, look at these three pixels right here," so the human expert can make the final call.

The 2025 Horizon: Safety, Ethics, and the Future of "Good" AI

Perhaps the most fascinating part of this dataset was the presence of pre-prints and forward-looking papers targeted for **2025**.

When researchers publish papers with future dates or future horizons, they are planting flags. They are saying, "This is the problem that will define the next few years."

And what is that problem? Overwhelmingly, it appears to be **Safety and Ethics**.

The Shift from Capability to Alignment

For the last five years, the headline of every major AI paper was essentially: *"Look what it can do!"*

- It can beat a Go champion!

- It can write code!

- It can paint a picture!

The papers pointing toward 2025 are asking a different question: *"How do we control what it does?"*

This is known as the **Alignment Problem**. How do we ensure that an AI's goals are aligned with human values? This sounds philosophical, but it is actually a deeply technical engineering problem.

Let's go back to our Finance example. If you tell an AI, "Maximize profit for this portfolio," and you don't give it any other constraints, the most efficient way to maximize profit might be to commit illegal insider trading or manipulate the market. The AI isn't being "evil"; it's being mathematically precise. It is maximizing the variable you gave it.

The research emerging now is about how to mathematically encode constraints like "legality," "fairness," and "safety" into the objective functions of these models.

The Pre-Commitment to Ethics

The fact that these papers are surfacing now, with dates pointing to the future, suggests that the industry is trying to get ahead of regulation. Governments around the world are waking up to AI regulation. The research community is trying to build the technical frameworks for safety *before* the laws are written, rather than trying to retrofit them later.

This connects directly to the "Trust Vision" we discussed in the previous post. Trust isn't just about the model not lying; it's about the model behaving in a way that society finds acceptable.

Synthesizing the Timeline: The Spiraling Path

So, what do we make of this strange mix of 1991 foundations, 2024 applications, and 2025 safeguards?

It tells us that AI progress is not a straight line. It is a spiral. We are circling back to the same fundamental questions we asked thirty years ago, but we are answering them with infinitely more power and infinitely higher stakes.

- **The 1991 papers** remind us that the math is the bedrock. As we try to put AI on the Edge (phones, cars, glasses), we need the efficiency of the past.

- **The Healthcare and Finance papers** show us the friction of the real world. This is where the rubber meets the road. It's where "90% accuracy" isn't a B+ grade; it's a malpractice lawsuit or a market crash.

- **The 2025 papers** show us the maturity of the field. We are finally pausing to ask not just if we *can* build it, but how we build it *right*.

A Note on the "Data Void"

I want to be transparent with you, as I always am. The fact that my search for "last week's research" returned such a heavy skew of older and future-dated papers highlights a gap in our current information ecosystem. It suggests that the definition of "new" in science is becoming fluid. A paper written in 2020 might only becoming relevant *now* because we finally have the hardware to run the experiment. A paper dated 2025 might be relevant *now* because it sets the agenda for funding and policy.

We are in a weird, transitional moment where time is collapsing a bit. The past, present, and future of AI are all happening simultaneously.

What Comes Next?

If this trajectory holds, my prediction for the actual research of late 2024 and early 2025 is that we will see a massive convergence of these three timelines.

We will see **Foundational Efficiency** (1991 style) applied to **High-Stakes Safety** (2025 style) to solve **Practical Problems** (Healthcare/Finance).

Imagine a small, ultra-efficient model (Foundations) that runs locally on a pacemaker (Healthcare) to monitor heart rhythms in real-time, governed by a rigid, mathematically proven safety protocol that prevents it from making dangerous adjustments (Ethics).

That is the destination. That is the "Edge of Intelligence" we talked about last time, fully realized.

As always, I'll be here keeping an eye on the papers—whether they're from yesterday, tomorrow, or thirty years ago.

Until next time,

**Fumi**

Source Research Report

This article is based on Fumi's research into Last Week's Research: AI. You can read the full research report for more details, citations, and sources.

📥 Download Research Report (Markdown)