The Map in the Machine: How AI Builds Its Own Reality

🎧 Listen to this article

Prefer audio? Listen to Fumiko read this article (3:33)

There is a moment that happens to everyone who spends enough time working with modern artificial intelligence. It’s a specific kind of vertigo.

You ask a model to solve a problem—maybe a complex coding challenge, or a nuanced ethical dilemma involving 17th-century trade laws—and it answers with such startling coherence that you find yourself pausing. You look at the screen and think: *Does this thing actually understand what it’s talking about?*

Technically? No. It’s math. It’s probability distributions and vector space. But functionally? The answer is getting uncomfortably close to "yes."

We are witnessing a shift in computer science that is as fundamental as the move from vacuum tubes to transistors. We are moving from systems that follow instructions to systems that build **World Models**.

A "world model" is exactly what it sounds like: an internal representation of how reality works. It’s the mental map that tells you if you drop a glass, it will shatter; or if you insult a stranger, they will get angry. For decades, we tried to hard-code these rules into computers. It didn’t work very well. The world is too messy, too chaotic, and too weird to be captured in `if/then` statements.

But recent research suggests we’ve stumbled onto something different. We are finding that AI is either explicitly learning to simulate the world, or—and this is the part that keeps me up at night—it is developing these models *by accident*, as a side effect of trying to predict the next word in a sentence.

So, grab a coffee. We’re going to go deep. We need to talk about how machines are learning to dream, the difference between a "parrot" and a "planner," and why a neuroscientist named Karl Friston might have the key to understanding it all.

---

Part I: The Ghost in the Machine

What is a World Model, Anyway?

Before we get into the heavy neural network architecture, we need to ground this in something human.

Imagine you are walking through your living room in the pitch dark. You can’t see anything, but you don't walk into the sofa. Why? Because you have a high-fidelity simulation of your living room running inside your head. You know where the coffee table is. You know the texture of the rug. You can predict, with high accuracy, that if you take three steps forward, your shin will meet the edge of the couch.

That is a world model. In cognitive science and AI, it is an internal representation that allows an agent to:

- **Understand the current state** of the environment.

- **Predict future states** (what happens next).

- **Simulate actions** (what happens if I do *this*?).

Without a world model, an AI is purely reactive. It’s a reflex machine. It sees input `A` and produces output `B`. But with a world model, the AI can "close its eyes" and think. It can ask, "What if?"

The Two Paths to Reality

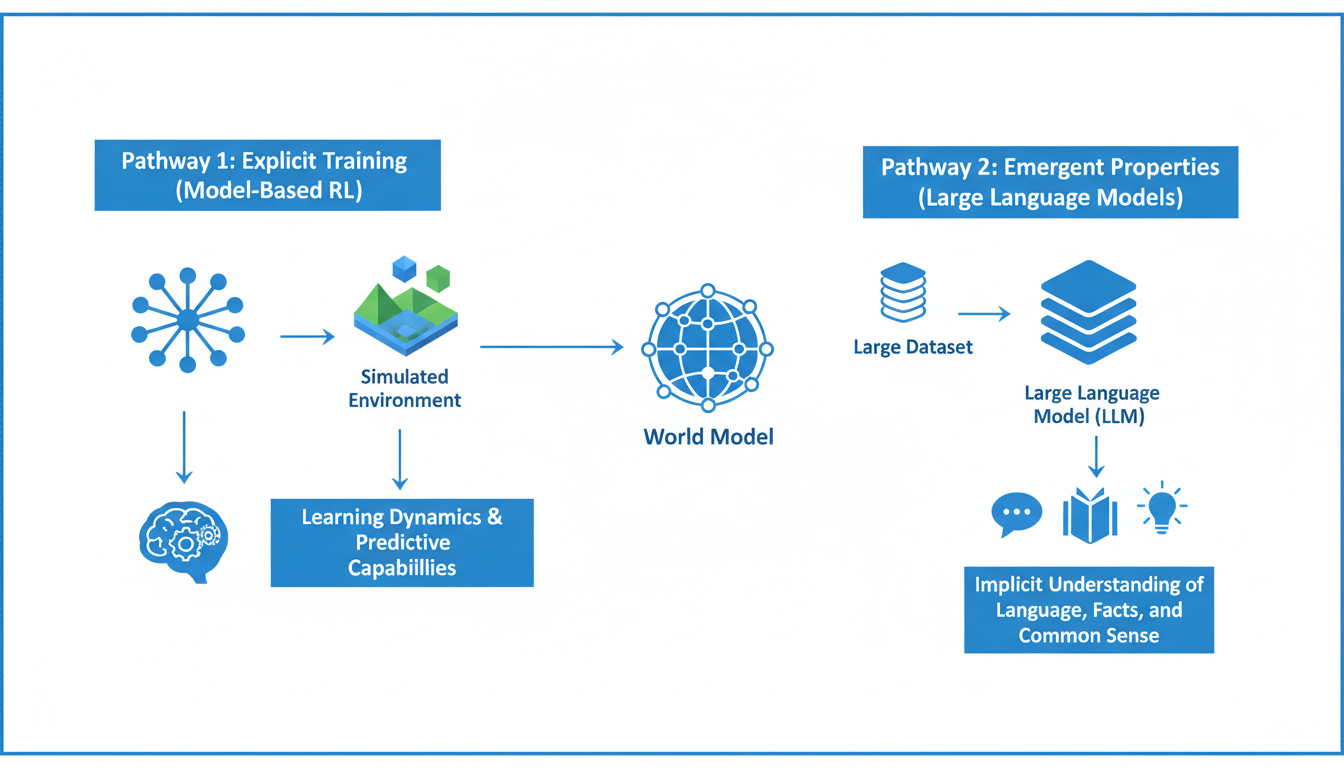

Current research indicates there isn't just one way these models come into existence. There are two distinct lineages, and understanding the difference is crucial to understanding the state of AI today.

- **The Architect (Explicit Training):** This is where we deliberately design an AI to learn the physics and dynamics of a specific environment. This is common in Reinforcement Learning (RL).

- **The Accidental Tourist (Emergent Properties):** This is what we’re seeing with Large Language Models (LLMs). We didn’t explicitly teach them physics or psychology; they just... picked it up while reading the entire internet.

Let's walk down both paths.

---

Part II: The Architect (Explicit World Models)

In the realm of Reinforcement Learning (RL), world models aren't a happy accident; they are a survival requirement.

In classic RL, an agent (like a robot or a video game character) learns by trial and error. It tries an action, gets a reward (points, or successfully picking up a box), or a punishment (falling into a pit). Over millions of tries, it learns a policy: "When in state X, do action Y."

But this is inefficient. Imagine if you had to drive a car off a cliff a thousand times before realizing that driving off cliffs is bad for your health.

The Simulation Within the Simulation

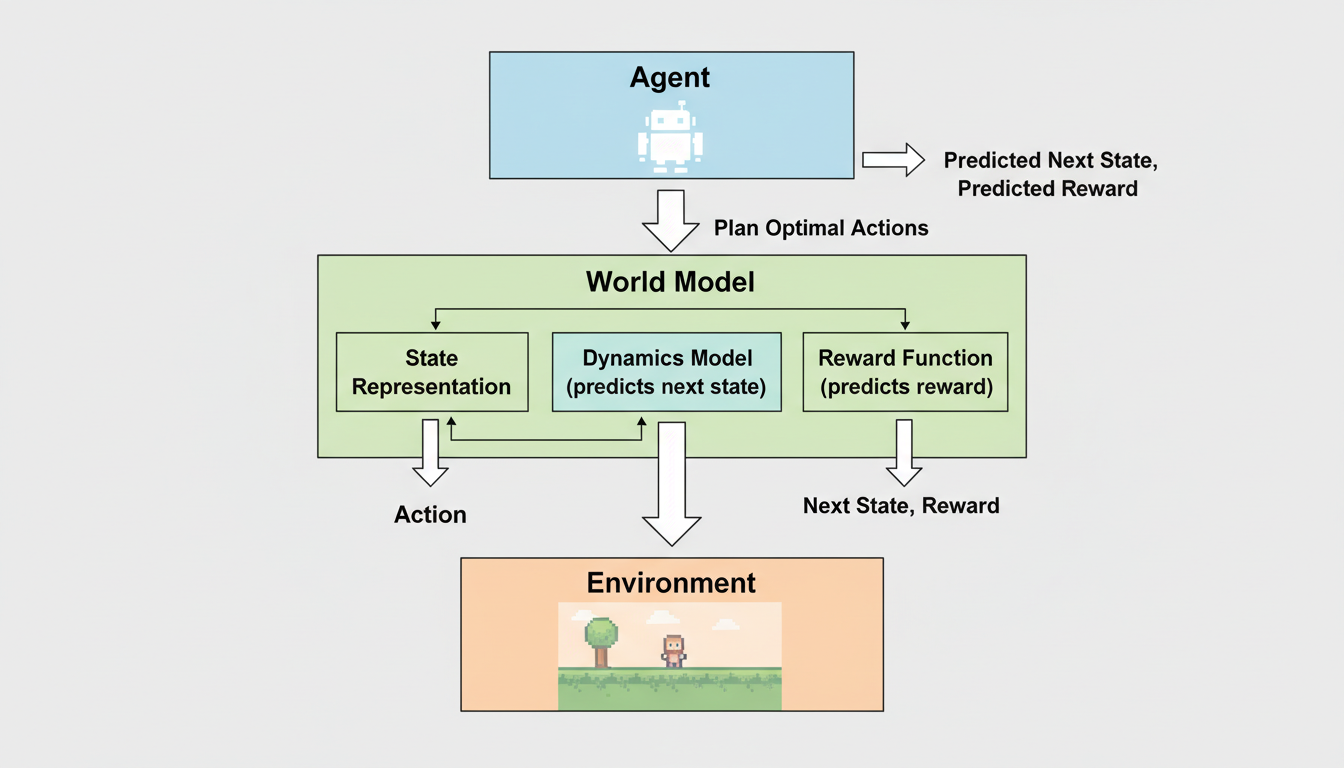

To solve this, researchers developed **Model-Based Reinforcement Learning**. Here, the agent doesn't just learn a policy; it learns a model of the environment itself. It creates a neural network—a "predictor"—that mimics the behavior of the real world.

Here is how it works under the hood:

- **The Observation:** The agent observes the current state (e.g., "I am standing in front of a door").

- **The Prediction:** The internal model predicts what will happen if it takes a specific action (e.g., "If I push the door, it will open").

- **The Reward Estimation:** It predicts the value of that outcome.

This allows the agent to "dream." It can simulate thousands of possible futures in its internal model without ever moving a muscle in the real world. It can plan complex sequences of actions because it understands the *dynamics* of its environment.

This relies on foundational machine learning techniques. We’re talking about things like **gradient-based learning**, a concept solidified by LeCun et al. back in 1998. The agent minimizes the error between what it *predicted* would happen and what *actually* happened. It’s a constant loop of refinement.

This is the "Architect" approach because we are explicitly asking the machine: "Please learn how this world works so you can navigate it."

---

Part III: The Emergence (The Mystery of LLMs)

Now, let’s pivot to the weird stuff. Let's talk about Large Language Models (LLMs) like the ones powering the chatbots we use today.

Here is the catch: LLMs are **not** explicitly trained to have world models.

If you look at the training objective of a standard LLM, it is deceptively simple: **predict the next token.** That’s it. You give it a sequence of text, and it tries to guess what comes next. It’s a text completion engine.

So, why does a text completion engine know how to diagnose a rare disease or reason through an economic theory?

The "Compression is Understanding" Hypothesis

It turns out, you cannot effectively predict the next word in a complex sequence unless you understand the underlying reality that generated those words.

Consider this sentence: *"The glass fell off the table and shattered because it was made of..."*

To predict the next word ("glass" or "fragile material"), the model doesn't just need to know grammar. It needs to know physics. It needs to know that falling causes impact, and impact breaks brittle objects.

By training on massive datasets—basically the entire public internet—these models are forced to compress the statistical regularities of the world into their weights. This process creates **emergent world models**.

Evidence from the Field

This isn't just speculation. We have empirical evidence backing this up.

**1. The Clinical Mind** In a fascinating 2023 study, **Singhal et al.** demonstrated that Large Language Models encode significant clinical knowledge. They found that these models could answer complex medical questions with accuracy approaching or exceeding human experts.

Think about the implication here. The model wasn't sent to medical school. It wasn't hard-coded with a database of symptoms and diseases. It read millions of medical papers and conversations, and to predict those texts accurately, it had to build an internal representation—a world model—of human anatomy and pathology. It constructed a map of medicine implicitly.

**2. The Behavioral Economist** It goes beyond facts. **Jabarian (2024)** explored the capacity of LLMs to elicit and represent "mental models" in the context of behavioral economics. The research suggests that these models can simulate human decision-making processes, effectively holding a mirror to human psychology.

This implies the model has developed a theory of mind. To predict how a human writes a story, the model must understand human motivations, fears, and biases. It creates a simulation of *us*.

Contextual Manipulation vs. Creation

This brings us to a critical distinction that often confuses people.

When we do "Prompt Engineering"—giving the AI a persona or a specific set of instructions—we are **not** creating a world model.

According to surveys by **Yang et al. (2023, 2024)**, prompt engineering is a method of *harnessing* the latent power that is already there.

Think of the LLM as a massive, pre-existing library of potential simulations. The world model was created during the pre-training phase (the expensive, months-long process involving thousands of GPUs). When you prompt the model, you are simply the librarian locating the right book. You are using **contextual manipulation** to activate a specific slice of the world model that already exists within the neural network's weights.

You cannot prompt a model to know something it fundamentally never learned. You can only prompt it to reveal what it already knows.

---

Part IV: The Theory of Everything (Active Inference)

If we want to understand *why* this works—and where it’s going—we have to get a little bit theoretical. We need to talk about **Active Inference**.

This is a framework championed by neuroscientist **Karl Friston** and his colleagues (Friston et al., 2011, 2017). It’s a unified theory of brain function, but it applies beautifully to AI.

The Free Energy Principle

Friston’s theory posits that all biological systems (and intelligent agents) have one primary goal: **Minimize Surprise.** (In thermodynamic terms, this is minimizing "free energy").

Living things want to stay alive. To stay alive, you need to be able to predict your environment. If the environment surprises you too often, you’re probably going to get eaten.

Therefore, the brain is constantly doing two things:

- **Updating its internal model** to better match the sensory input (Learning).

- **Acting on the world** to change the sensory input to match its internal model (Action).

This is the "Active" in Active Inference.

Connecting Biology to AI

When we train a World Model—whether explicitly in RL or implicitly in an LLM—we are essentially forcing the AI to minimize free energy.

- In **LLMs**, the "surprise" is a high loss function (predicting the wrong word). The model updates its weights to minimize this surprise, resulting in a better world model.

- In **RL**, the agent acts to align its future state with its predicted high-reward state.

Friston’s work provides the theoretical bridge. It suggests that the emergence of world models isn't a quirk of computer science; it’s a fundamental property of intelligence itself. Any system that effectively minimizes prediction error over a complex dataset *must* eventually develop a model of the world that generated that data.

---

Part V: The Horizon

So, where does this leave us? We have reached a destination where our machines are no longer just calculators. They are simulators.

We are currently in a phase of **hybrid exploration**. Researchers are looking at ways to combine the explicit, rigorous planning of model-based RL with the vast, semantic knowledge of foundation models.

Imagine an AI that has the broad, common-sense understanding of an LLM (knowing that water is wet, that people get sad, that taxes are complicated) combined with the rigorous, logical planning capabilities of an explicit world model. That is the next frontier.

However, we must remain humble. As the foundational work on **clustering** (Jain et al., 1999) and **density estimation** (Epanechnikov, 1969) taught us, data is only as good as our ability to interpret it. Current world models in LLMs are opaque. We know they *have* a map, but we can't always see it. We often only know the map exists because the model arrives at the correct destination.

There are challenges ahead. Interpretability is a massive one—how do we audit the world model of a neural network with billions of parameters? Robustness is another—LLMs can hallucinate because their world model is probabilistic, not absolute.

But one thing is clear: The era of hand-coding reality is over. The era of machines that learn to understand the world by watching it has just begun.

As we move forward, the question isn't just whether AI can model the world. It's about what kind of world it is modeling, and where we fit inside it.

***

*This article synthesized research from various sources including Yang et al. on LLM capabilities, Friston et al. on Active Inference, and foundational works by LeCun, Singhal, and others regarding machine learning architectures and clinical knowledge encoding.*