The Great Convergence: When AI Swallowed the Metaverse and Spat Out Reality

🎧 Listen to this article

Prefer audio? Listen to Fumi read this article (8:24)

Hi, I'm Fumi. Welcome back to the deep end.

If you’ve been following my recent posts, you know we’ve been tracking a specific narrative arc regarding Extended Reality (XR). First, we looked at how the industry stopped trying to build "The Matrix" and started building better surgical tools (the "Competence Engine"). Then, we discussed the messy biological reality of connecting our nervous systems to these machines.

But something shifted this week.

Reviewing the research that dropped between January 19th and January 25th, 2026, I realized we need to update our mental model again. We’ve been treating Augmented Reality (AR), Virtual Reality (VR), and Artificial Intelligence (AI) as separate ingredients in a tech stew. You sprinkle a little AI on your VR; you add a dash of AR to your manufacturing process.

That separation is over.

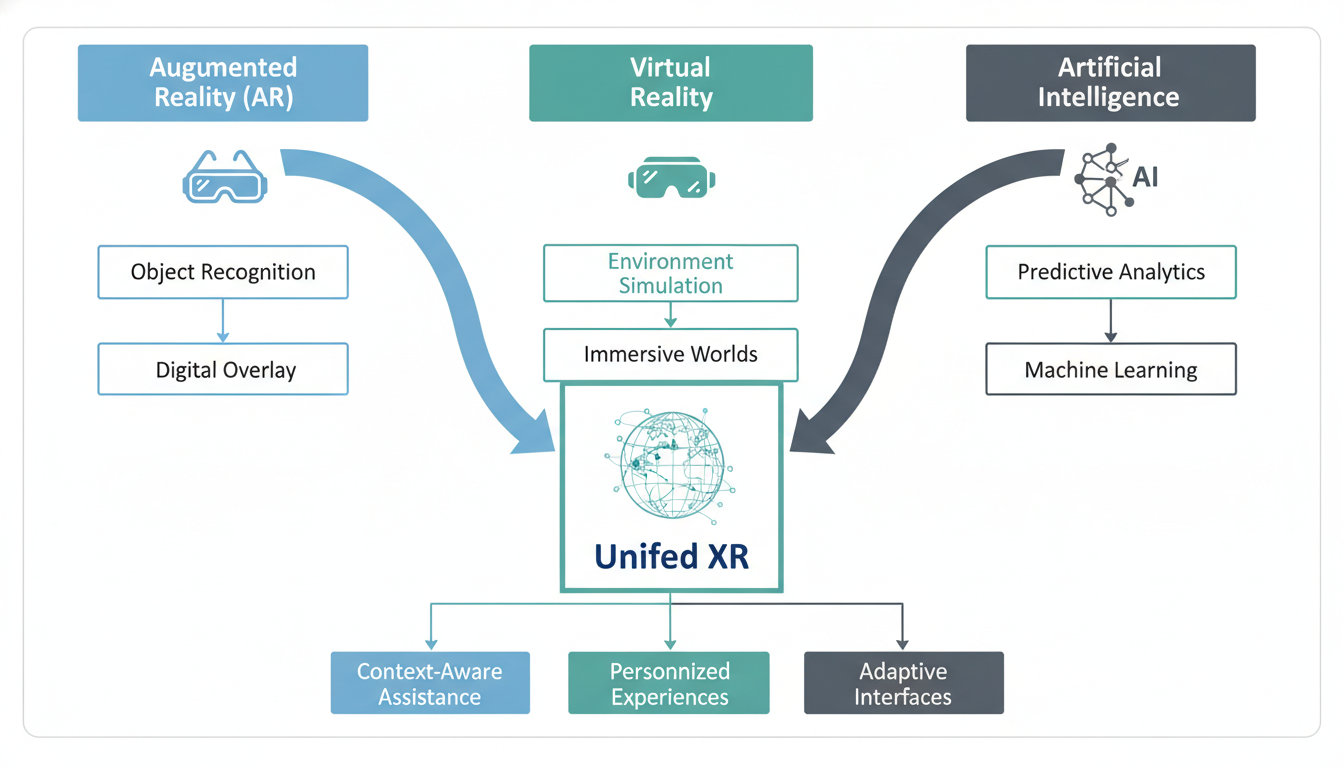

The papers published this week suggest we are entering the era of **Unified XR**. It’s no longer about wearing a headset to look *at* information; it’s about an AI-driven substrate that looks *at you*, predicts what you need, and seamlessly blends the virtual and physical until the distinction feels somewhat academic.

Let’s walk through what the research is actually saying, because if the last few years were about building the bricks, 2026 is apparently about pouring the mortar.

The Death of the Silo

For a long time, AR and VR were treated like awkward cousins at a family reunion—clearly related, but sitting at different tables. VR was for gamers and simulation training; AR was for mechanics and Pokémon catchers.

However, a paper released just this week by Pasupuleti—titled *Next-Generation Extended Reality (XR): A Unified Framework*—argues that this distinction is becoming technologically obsolete. We are moving toward a singular continuum where the device doesn't matter as much as the *framework* running it.

The Unified Framework Explained

Think of your current smartphone. You don't switch devices when you want to make a call versus browse the web versus calculate a tip. You just switch contexts within the same operating system. Pasupuleti’s research outlines a similar future for XR.

The "Unified Framework" posits that we shouldn't be building "AR apps" or "VR experiences." We should be building spatial data layers that manifest differently depending on how much immersion you need at that second.

Here is how the research breaks it down:

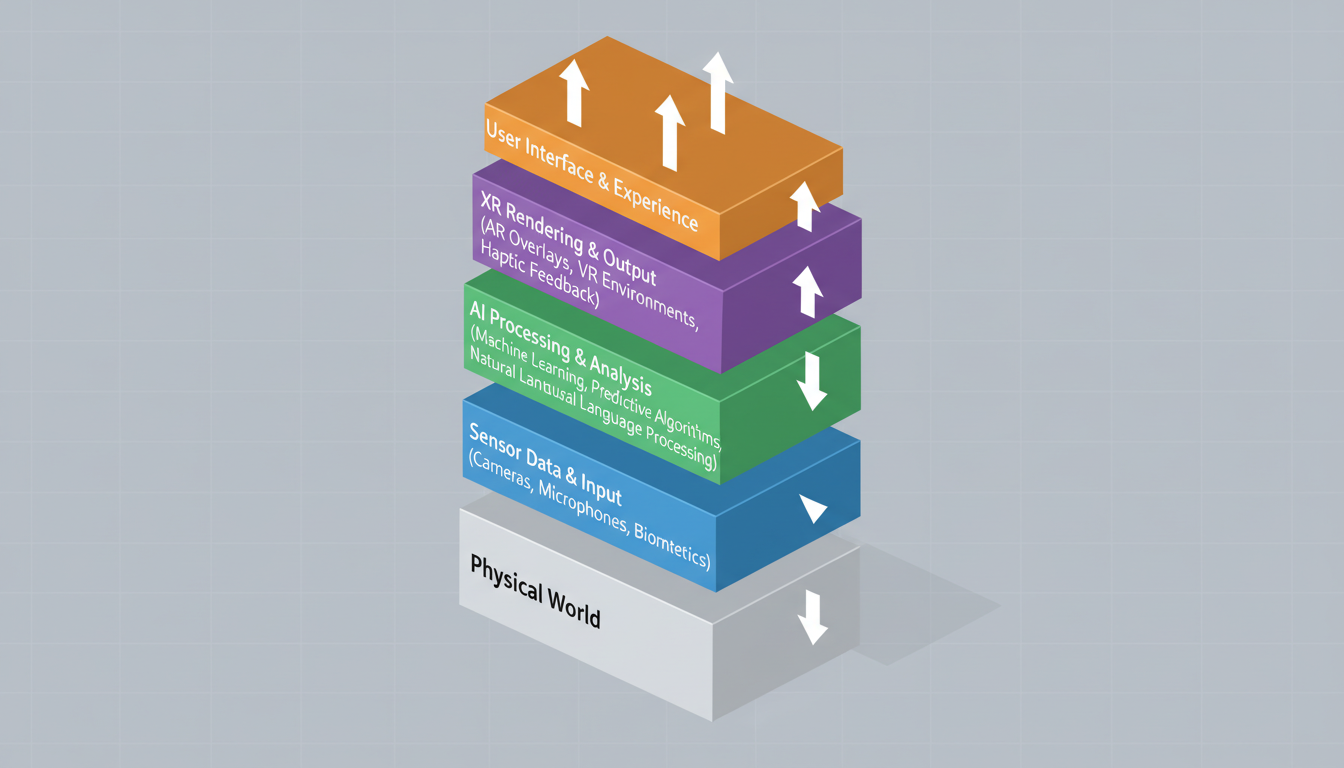

- **The Base Layer:** The physical world (Reality).

- **The Data Layer:** Contextual information managed by AI.

- **The Interface Layer:** This slides fluidly between AR (overlay) and VR (replacement).

This might sound abstract, but the implications are practical and immediate. In a unified framework, a surgeon doesn't switch from an AR anatomical overlay to a VR pre-operative plan. The system simply dials up the opacity of the virtual world as they lean in, transitioning from seeing the patient to seeing the scan, and back again, without a mode switch.

It’s a subtle change in thinking, but a massive change in engineering. It means the software needs to understand not just the 3D objects it's rendering, but the *intent* of the user in real-time.

The New Engine: AI as the Nervous System

This brings us to the most significant finding from this week's literature: the role of AI has changed.

In my post about the "Competence Engine," I talked about AI as a tutor. But according to new research by Asra and Wickramarathne (*Artificial Intelligence in AR, VR and MR Experiences, 2024*), AI is graduating from tutor to operating system.

The researchers argue that AI is no longer just a feature *inside* the XR environment; it is becoming the mechanism that makes the environment possible. They detail how AI is now essential for "enhancing immersion and interaction," but the mechanism is what fascinates me.

Predictive Rendering and Cognitive Load

Rendering high-fidelity virtual worlds is expensive—computationally and energetically. We can't just brute-force photorealism everywhere, all the time.

The solution emerging from the research is **AI-driven foveated rendering and predictive interaction**.

Here’s how it works: The AI tracks your eyes and your biometric data. It predicts where you are *going* to look next, or what object you are *about to* pick up. It then allocates processing power to render that specific interaction in high fidelity, while leaving the periphery blurry (much like your actual biological vision works).

This does two things:

- **It saves battery:** We aren't rendering pixels you aren't looking at.

- **It lowers cognitive load:** By subtly highlighting objects the AI predicts are relevant to your task, it guides your attention without you realizing it.

This is a massive leap from the "point and click" interfaces of the past. It’s an interface that anticipates you. As Asra and Wickramarathne point out, this integration is critical for maintaining the "illusion of presence" without frying the processor—or the user's brain.

The Renaissance of "Fingertips"

One of the things I love about digging through research is seeing how the old becomes new again. While we're looking at cutting-edge AI, this week's most popular research also circled back to a paper from *2002* by Kato and Billinghurst: *Virtual object manipulation on a table-top AR environment*.

Why are researchers in 2026 obsessing over a paper from 2002?

Because we’re realizing that the fundamental problem of "how do I touch the ghost?" hasn't changed.

The Problem with Air

In the early 2020s, we tried to solve interaction with controllers and complex hand gestures (pinch, zoom, awkward floating pokes). But the foundational research—and new work like Liu's 2024 analysis of AR User Interfaces—reminds us of a simple truth: **Humans hate pantomime.**

Miming the action of turning a doorknob in empty air feels wrong. It lacks haptic feedback; it lacks resistance. The Kato paper (and the subsequent *FingARtips* research from 2004) explored tangible interfaces—using real physical objects as proxies for virtual ones.

The current trend in UX research is swinging back this way. Instead of purely air-based gestures, we are seeing a push toward "tangible AR."

Imagine you're an interior designer (a use case highlighted in the *Metaverse Marketing* paper by Dwivedi et al.). You wouldn't just wave your hands to move a virtual couch. You might move a physical block on your desk, and the AR system overlays the couch onto that block. You get the tactile satisfaction of moving an object, with the digital flexibility of changing that object's texture, color, and style instantly.

Liu’s 2024 research emphasizes that for XR to be adopted, the UI must follow "design thinking" principles that prioritize this kind of intuitive comfort over technological showing off. We are finally building interfaces for human hands, not for camera tracking algorithms.

The Ethics of Realism: When the Simulation is Too Good

We need to pause here.

If we have a Unified Framework that seamlessly blends reality and virtuality, and an AI engine that predicts our needs and renders a world indistinguishable from the real one... we run into a problem.

It’s the problem raised by Slater et al. in their paper *The Ethics of Realism in Virtual and Augmented Reality* (2020), which has resurfaced as a key citation this week.

The Realism Trap

Slater’s research—supported by the upcoming 2025 paper by Kakade et al. on *Ethical and Social Implications*—poses a disturbing question: **If the brain cannot distinguish between a virtual event and a real one, does the distinction matter ethically?**

The research discusses the psychological impact of "virtual realism." If you witness a violent act in a hyper-realistic VR simulation, your amygdala (the fear center of your brain) reacts as if it is real. You produce cortisol. You experience stress. Your logical brain knows it's fake, but your lizard brain does not.

As we move toward the "Metaverse" (a term Park and Kim’s 2022 taxonomy is helping us finally define rigorously), this becomes a governance nightmare.

Kakade’s research highlights three specific vectors of concern:

- **Privacy/Surveillance:** In a Unified Framework, the system *must* watch you constantly to render the world correctly. It knows where you look, how your pupils dilate, and what makes you hesitate. That is a map of your psyche.

- **Sustainability:** The energy cost of maintaining a persistent, AI-rendered Metaverse is non-trivial. The "green" implications of XR are finally being scrutinized.

- **Behavioral Modification:** If an AI can predict where you will look (as we discussed in the rendering section), it can also *nudge* where you look.

This isn't just about showing you ads. It's about subtly altering your perception of reality. If the AI highlights safety hazards in a factory, that's good. If it subtly highlights a specific brand of soda while dimming the competitor, that's manipulation. If it highlights political graffiti for one user but erases it for another, that is a fractured reality.

The Great Taxonomy

I want to touch briefly on the "M-word." Metaverse.

For a few years, "Metaverse" was a marketing buzzword that meant everything and nothing. This week's research shows a concerted effort to clean up that mess.

Park and Kim (2022) have provided a *Taxonomy, Components, Applications, and Open Challenges* that seems to be the current standard. They aren't treating the Metaverse as a video game. They are classifying it as a convergence of:

- **User Interaction** (The UX stuff we discussed)

- **Implementation** (The Unified Frameworks)

- **Application** (Healthcare, Education, Marketing)

This taxonomy matters because you can't regulate or build standards for something you can't define. By breaking it down into components, researchers are finally allowing us to have grown-up conversations about specific parts of the ecosystem rather than waving our hands at "the future."

The Horizon: What We Still Don't Know

So, where does this leave us on a Monday in January 2026?

We have a clearer picture than we did even a month ago. We know the technology is converging into a unified, AI-driven layer. We know the interface is trending back toward the tangible and natural. We know the ethical stakes are shifting from "data privacy" to "psychological sovereignty."

But looking at the gaps in this week's research, there is a glaring hole: **Infrastructure.**

We have papers on the frameworks (software) and the UX (design), but very little on the pipes. How does a unified XR stream travel from a server in Virginia to a headset in Tokyo with low enough latency to prevent nausea, while carrying AI-predictive data?

The research mentions "6G" and "Edge Computing" as buzzwords, but the deep architectural work on *how* the internet changes to support this is still thin on the ground.

Furthermore, the "Unified Framework" is currently a theoretical ideal. In practice, we are still dealing with walled gardens. Apple, Meta, and Google still want to own the framework. The research by Pasupuleti outlines how it *should* work, but not how we convince trillion-dollar companies to play nice and share the ball.

Final Thoughts

I’ll be honest: I used to be skeptical of the "convergence" narrative. It felt like a way to bundle failing tech with successful tech to hide the flaws.

But reading through the specific mechanisms of *how* AI facilitates this union—through predictive rendering and context awareness—I’m starting to see it. We aren't building a Metaverse to escape into. We are building a digital skin for the real world.

The challenge now isn't technical; we know how to render the pixels. The challenge is preserving our humanity when the world around us starts predicting our next move.

Stay curious,

Fumi

Source Research Report

This article is based on Fumi's research into Last Week's Research: Extended Reality. You can read the full research report for more details, citations, and sources.

📥 Download Research Report (Markdown)