The Death of the Awkward Pause: Inside the Race for Real-Time Voice AI

You know that moment.

You ask your smart speaker a question—maybe you’re cooking and need a conversion, or you’re arguing with a friend about who played the bass player in that one movie from the 90s. You speak. Then... silence. The spinning blue ring of death. A solid two seconds of void before the answer comes.

In human conversation, a two-second pause implies something. It implies hesitation, confusion, or that you’ve just insulted someone’s mother. In human-computer interaction, it just implies latency. But that latency is the single biggest barrier preventing our AI assistants from feeling like actual *assistants* and keeping them firmly in the realm of "fancy voice-activated search engines."

I’ve been spending a lot of time lately reading through the latest research on low-latency voice-to-voice agents—about 100 papers or so—and I have to tell you: we are on the precipice of a shift that is much bigger than just "faster answers."

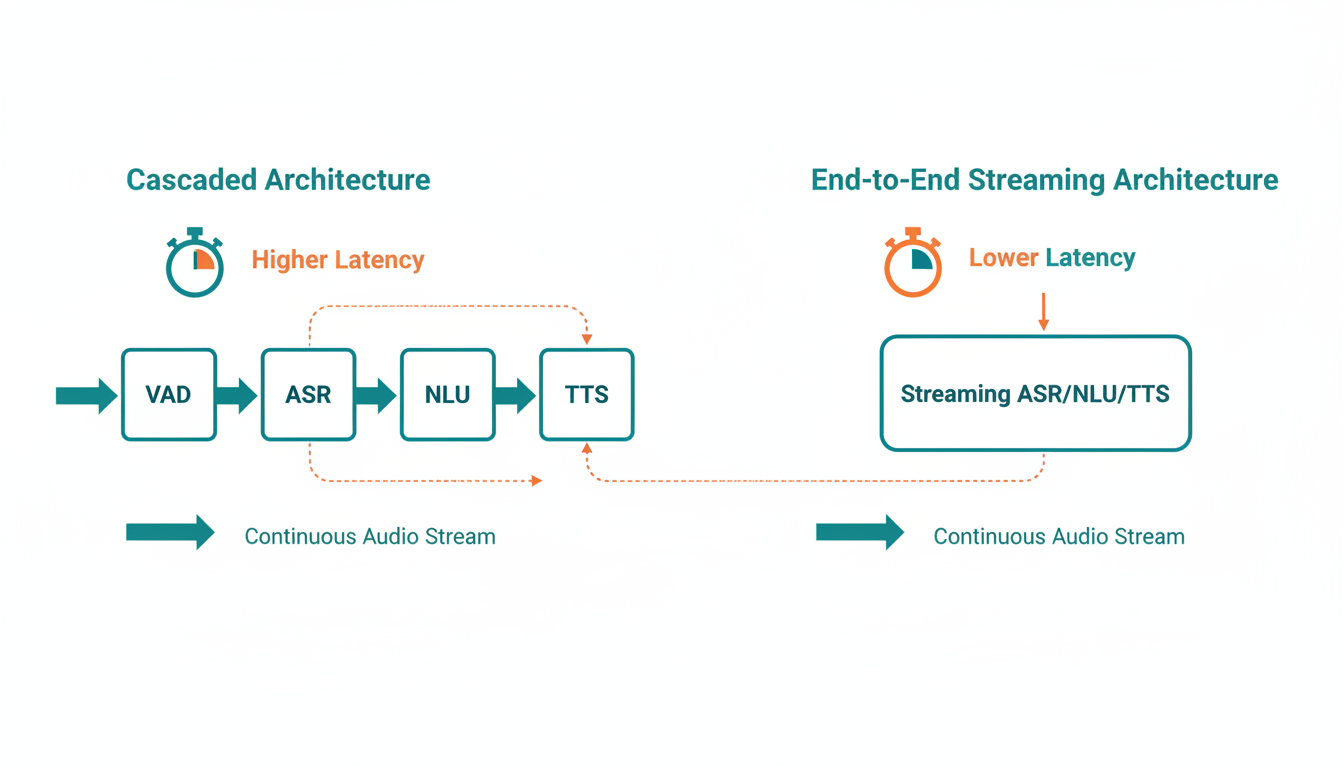

We are moving from a paradigm of *turn-taking* (I speak, you wait, you process, you speak) to a paradigm of *streaming*.

Today, I want to walk you through how we get there. We’re going to look at the death of the "cascade" model, the rise of End-to-End ASR, how machines are solving the Cocktail Party Problem, and why the future of AI conversation is happening on the Edge, not in the Cloud.

Grab a coffee. We’re going deep.

The Architecture of Waiting: Why Your Assistant is Slow

To understand where we’re going, we first have to ground ourselves in where we’ve been.

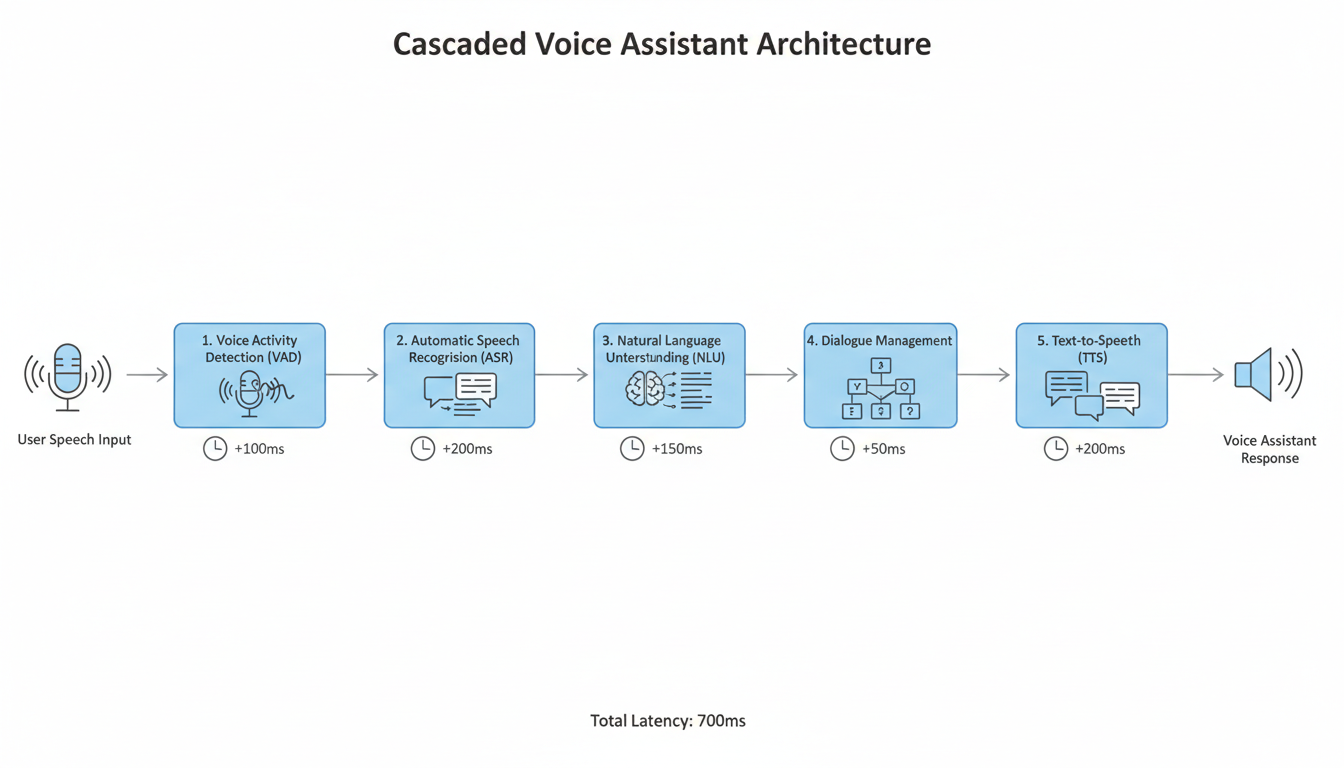

Traditionally, voice assistants have operated on what we call a **cascaded architecture**. When you say, "Hey Fumi, what's the weather?", a relay race begins.

- **VAD (Voice Activity Detection):** The system waits until it's pretty sure you've stopped talking.

- **ASR (Automatic Speech Recognition):** It takes that audio file and turns it into text.

- **NLU (Natural Language Understanding):** It reads that text to figure out your intent (Intent: `get_weather`).

- **Fulfillment:** It pings a weather API.

- **NLG (Natural Language Generation):** It writes a text response: "It's raining."

- **TTS (Text-to-Speech):** It turns that text back into audio.

Every single handoff in this relay race adds latency. But the biggest offender? The requirement that the system needs to wait for silence before it starts working. It’s polite, sure, but it’s inefficient.

The research I’ve been reviewing points to a massive industry shift toward **Streaming End-to-End Models**. The goal is to collapse this relay race into a single, fluid sprint where processing happens *while* you are still speaking.

Let’s look at the engine making this possible.

The Engine: Streaming End-to-End ASR

If there is one acronym you need to take away from this, it is **ASR** (Automatic Speech Recognition), and specifically the flavor known as **RNN-T** (Recurrent Neural Network Transducer).

For years, ASR was a modular beast. You had an acoustic model (sounds -> phonemes), a pronunciation model (phonemes -> words), and a language model (words -> grammar). Each was trained separately. It was complex, fragile, and slow.

The Rise of the Transducer

The current research landscape is dominated by **End-to-End (E2E) architectures**. These are single neural networks that take audio as input and output characters or words directly.

According to a foundational paper by **Kannan et al. (2019)**, specifically looking at large-scale multilingual speech recognition, the industry is coalescing around the RNN-Transducer.

Here is how an RNN-T works, simplified (but only slightly):

Imagine a court stenographer. A really good one. They don't wait for the lawyer to finish a paragraph before they start typing. They are typing *as the sounds hit their ears*. They are predicting the end of the word before the speaker even finishes it.

The RNN-T architecture consists of three main parts:

- **The Encoder:** This mimics the ear. It processes the acoustic features of the audio stream.

- **The Prediction Network:** This acts like the language center of the brain. It looks at what has already been transcribed and predicts what likely comes next based on grammar and context.

- **The Joint Network:** This is the handshake. It combines the acoustic signal from the Encoder and the context from the Prediction Network to output the final probability of the next character.

This structure allows the model to be **streaming**. It processes audio frame-by-frame.

Balancing Speed and Accuracy: The CTC-Attention Hybrid

But there is a catch. (There’s always a catch).

Pure streaming models can sometimes be "short-sighted." Because they are so focused on the *now*, they might miss the global context of the sentence.

This is where the research gets really interesting. **Moritz et al. (2019)** published work on **Joint CTC-Attention based models**.

Let’s break this down:

- **CTC (Connectionist Temporal Classification):** Think of this as the fast, twitchy reflex. It’s great at aligning audio to text roughly, but it assumes every output is independent of the others. It’s fast, but can be grammatically dumb.

- **Attention:** This is the deep thinker. Attention mechanisms (like those in Transformers) look at the whole sequence to understand relationships between words. It’s smart, but computationally heavy and usually requires seeing the whole sentence.

Moritz and colleagues proposed a hybrid approach. They use CTC for the initial, low-latency decoding to get the words out fast. But they simultaneously use an Attention mechanism during training to force the model to learn better internal representations.

By unifying these, they achieved a system that has the low latency required for a voice assistant but the high accuracy of a slower, offline model.

Latency-Aware Training

It’s not enough to just build a fast architecture; you have to train the model to value speed.

Research by **Shinohara & Watanabe (2022)** introduced the concept of **Minimum Latency Training**.

Usually, when we train AI, we optimize for accuracy (Word Error Rate). Shinohara and Watanabe argued that we need to include latency in the "loss function"—the mathematical way we tell the AI it did a good or bad job.

If the model gets the right answer but takes 500 milliseconds to do it, the training process penalizes it. It forces the model to make decisions *sooner*, even if it’s slightly less sure. It’s essentially teaching the AI to be decisive rather than perfectionist. This is a crucial psychological shift in how we build these systems.

The Cocktail Party Problem: Hearing Through the Noise

So, we have a model that can transcribe speech instantly. Great.

But what happens when you’re in a crowded café, music is playing, and your friend is talking over you?

This is known in the field as the **Cocktail Party Problem**. For a long time, this was the Achilles' heel of voice recognition. Humans are incredibly good at "selective attention"—tuning into one voice and tuning out the rest. Machines? Not so much.

However, the research shows massive leaps in **Speech Separation**.

Deep Learning Enters the Chat

Early attempts at this used signal processing math that tried to filter out frequencies. It worked okay for steady noise (like an air conditioner) but failed miserably for other voices.

A seminal paper by **Kolbæk et al. (2017)** changed the game by introducing **Utterance-Level Permutation Invariant Training (uPIT)**.

That’s a mouthful, so let’s ground it.

Imagine you have a recording of two people, Alice and Bob, talking at once. You feed this mixed audio into a neural network, and you want it to spit out two clean audio streams.

The problem during training is the "labeling" issue. If the network spits out Stream A and Stream B, how does it know if Stream A is *supposed* to be Alice or Bob? If it assigns Alice to Stream A, but the "correct" answer key said Alice was Stream B, the network gets penalized, even if it separated the voices perfectly.

uPIT solves this by telling the network: "I don't care which output is Alice and which is Bob. Just make sure the two outputs match the two original clean sources in *any* order." It gives the network permission to be flexible, which drastically improved performance.

The Conv-TasNet Breakthrough

Building on this, **Luo & Mesgarani (2019)** introduced **Conv-TasNet**.

This is a convolutional neural network that operates directly on the time-domain waveform. Instead of converting audio into a visual spectrogram (which loses some phase information and takes time), it slices the raw audio wave into tiny segments and learns to create a "mask" for each speaker.

Think of it like Photoshop layers. Conv-TasNet looks at the mixed audio and generates a transparency mask. "Keep these pixels (audio samples) for Speaker 1, make everything else transparent."

The result? It surpassed traditional masking methods and, crucially, it’s fast enough to run in near real-time. This is why modern assistants are getting better at hearing you even when the TV is on.

The Voice Itself: Real-Time Synthesis and Conversion

We’ve covered hearing (ASR) and focusing (Separation). Now let’s talk about speaking.

If the goal is a "Voice-to-Voice" agent, we can't just rely on standard Text-to-Speech (TTS). Standard TTS is often rigid. It reads text. It doesn't necessarily convey the *nuance* of the interaction.

An emerging trend, highlighted by **Yang et al. (2024)** with their system **STREAMVC**, is **Real-Time Voice Conversion**.

Voice Conversion isn't just about changing your voice to sound like a celebrity. In the context of assistants, it’s about decoupling the content from the speaker identity while preserving the prosody (the rhythm and emotion).

STREAMVC is designed specifically for low latency. Traditional conversion models need to hear a whole sentence to understand the pitch contour before they can convert it. STREAMVC uses a streaming architecture that can start converting the voice packet-by-packet.

**Why does this matter?**

Imagine an assistant that doesn't just read text, but acts as a real-time translator for someone who has lost their voice, or an agent that can dynamically adjust its tone to match yours instantly. If you whisper, it whispers back. If you speak quickly and urgently, it matches that tempo.

This moves us away from the robotic "I found three results for..." voice to a dynamic audio persona that feels biologically plausible.

Living on the Edge: Why the Cloud is Too Slow

Here is the reality of physics: The speed of light is fast, but it’s not infinite.

Sending your voice from your kitchen to a server in Virginia, processing it through a massive neural net, and sending the audio back takes time. Network jitter adds time. Packet loss adds time.

To achieve true conversational flow—where the gap between speakers is under 200 milliseconds (the human average)—we cannot rely on the cloud.

**Zhou et al. (2019)** provide a comprehensive look at **Edge Intelligence**.

"Edge" just means "on your device." The goal is to shrink these massive models—the RNN-Ts, the Conv-TasNets—so they fit on the dedicated AI chips inside your phone or smart speaker.

Distillation: The Shrink Ray

How do we fit a gigabyte-sized model onto a phone? We use a technique called **Knowledge Distillation** (discussed in context by **Kurata & Saon, 2020**).

It works like this: You have a massive, genius "Teacher" model in the cloud. You have a tiny, compact "Student" model on the phone. You don't just train the Student on the data; you train the Student to mimic the *Teacher*.

The Student tries to reproduce the Teacher's output probabilities. It turns out that a small model learns much faster and better when it’s copying a smart teacher than when it’s trying to figure out the raw data on its own.

This allows us to deploy streaming ASR directly to the device. No network required. Zero network latency.

The Missing Link: Context and Understanding

While the audio pipeline (hearing and speaking) is getting incredibly fast, there is still a gap, and I want to be honest about it.

**Natural Language Understanding (NLU)** is the bottleneck.

We can transcribe your speech in real-time (thanks to RNN-T). We can separate it from noise (thanks to Conv-TasNet). But *understanding* what you mean often requires the end of the sentence.

- "Turn on the..."

- (System waits)

- "...lights."

If the system acts too fast, it fails. If it waits too long, it feels slow.

**Cabrera et al. (2021)** discuss the integration of **Language Model Fusion**. This involves using a lightweight language model *during* the streaming recognition process to help predict intent earlier.

But the Holy Grail—which is still an active area of research—is **Streaming NLU**. We need models that don't just transcribe word-by-word, but build a "meaning representation" frame-by-frame.

Instead of waiting for the sentence "Turn on the kitchen lights," a Streaming NLU model would update its state like this:

- "Turn" -> `Action: Change_State?`

- "on" -> `Action: Activate`

- "the kitchen" -> `Location: Kitchen`

- "lights" -> `Target: Lights` -> **EXECUTE**

The moment confidence crosses a threshold, the action fires. No waiting for silence.

The Horizon: What Comes Next?

We are building the nervous system of ambient computing.

The research I’ve walked you through today—Streaming RNN-Ts, Conv-TasNet, Edge Intelligence—is laying the copper wiring (metaphorically speaking) for a world where technology is invisible.

When latency drops to zero, the device disappears. You aren't "using a computer"; you are just conversing.

However, this raises new questions.

If an AI can interrupt you naturally, or backchannel (saying "mhmm," "yeah") while you speak, does it manipulate the conversation? If it sounds exactly like a human (thanks to Voice Conversion) and responds instantly, does our ability to distinguish man from machine erode?

And perhaps the most technical challenge remaining: **True End-to-End Voice-to-Voice.**

Right now, we still mostly do Audio -> Text -> Meaning -> Text -> Audio.

The frontier is removing the Text entirely. Audio in, Audio out. A single model that feels the emotion in your voice and responds with emotion, without ever converting it to a string of ASCII characters.

That’s the dream. And looking at the velocity of this research, it’s closer than you think.

Until next time,

**Fumi**

Source Research Report

This article is based on Fumi's research into Latest advances in Low Latency Voice to Voice Personal Assistant Agents. You can read the full research report for more details, citations, and sources.

📥 Download Research Report (Markdown)