The Architecture of Connection: Why the Metaverse is Finally Getting Real (And Why We Still Might Throw Up)

🎧 Listen to this article

Prefer audio? Listen to Fumi read this article (10:53)

Hello, friends. Fumi here.

It’s Sunday, January 18, 2026.

If you’ve been following along with my recent deep dives into the state of Extended Reality (XR), you know we’ve been on a bit of a journey. Two weeks ago, in *“The Utility Era,”* we talked about how XR stopped trying to be a sci-fi escape hatch and started optimizing our actual reality. Last week, in *“The Competence Engine,”* we explored how these tools are fundamentally rewiring how we learn skills, from surgery to engine repair.

I thought we had a handle on the narrative: XR is a tool. It’s a wrench, not a world.

But after spending the last few days buried in this week’s research stack—99 papers, to be precise, covering everything from mobile anatomy lessons to the theoretical limits of 6G networks—I have to admit something: I might have been thinking too small.

We aren't just building better wrenches. We are building a nervous system for the planet, and a new social fabric for ourselves. The research this week pivots hard from "how do use this tool?" to "how do we live inside this system?"

We’re seeing the convergence of Digital Twins, hyper-advanced educational psychology, and—perhaps most surprisingly—genuine social connection. But we’re also slamming face-first into some stubborn biological and technical walls. Specifically, our inner ears still hate us, and our networks aren't quite fast enough.

So, grab your coffee (or your ginger tea, if you’re prone to motion sickness). Let’s dig into the architecture of connection.

Part 1: The Loneliness Paradox

For years, the lazy critique of the Metaverse (and XR in general) was that it would isolate us. We’d all be sitting alone in dark rooms, strapped into headsets, ignoring the real humans next to us while chasing digital butterflies. It was a *Wall-E* dystopia waiting to happen.

However, a fascinating study by Oh et al. (2022) that surfaced in this week’s popular research challenges that narrative head-on. The researchers looked at the relationships among social presence, supportive interaction, and feelings of loneliness. Their findings suggest something counter-intuitive: living in the metaverse can actually offer significant social benefits.

The Mechanics of "Being There"

To understand why, we have to talk about **Social Presence**. In the academic sense, this isn't just about having a chat box open. It’s the psychological state where technology becomes transparent, and you feel like you are genuinely *with* another person, even if they are physically a continent away.

When you text someone, you are communicating. When you inhabit a shared virtual space with them, see their avatar nod, track their gaze, and share an experience, you are *co-presenting*. The research indicates that this high-fidelity social presence fosters "supportive interaction"—the kind of meaningful engagement that actually moves the needle on emotional well-being.

This isn't just about gaming. Think about the "Competence Engine" concept I discussed last week. We focused on learning skills, but we missed the mentorship angle. If a senior surgeon in Tokyo can guide a resident in New York, and they both feel like they are standing at the same operating table, that’s not just data transfer. That’s a human connection. That’s mentorship. That reduces the professional isolation that so many remote workers feel.

The Revisit Intention

Ghali et al. (2023) added another layer to this by exploring how marketing and consumer presence work in these spaces. They found that "attachment" is a key driver for why people come back. We aren't returning to these worlds for the graphics; we're returning for the *feeling* of the space and the people in it.

**My read on this:** We need to stop viewing XR solely as a visual medium. It is an empathetic medium. The "killer app" for the Metaverse isn't a game or a workspace; it's the ability to kill distance. But—and this is a massive "but"—this only works if the technology disappears. If you're fighting the interface, the illusion breaks. Which brings us to the education sector, where the interface is finally starting to vanish.

Part 2: The Cognitive Load Revolution

If you read my post on *"The Competence Engine,"* you know I'm obsessed with how XR is changing vocational training. But this week’s research provided the *why* behind the *what*.

We have a stack of papers—Küçük et al. (2016), Thees et al. (2020), and a systematic review by Buchner et al. (2021)—that all circle the same drain: **Cognitive Load Theory**.

The Biology of Learning

Let’s ground this. Your working memory is a bucket with a hole in it. You can only hold so much information at once before it starts spilling out.

In traditional education, particularly for complex spatial subjects like anatomy or physics, a huge amount of your "bucket" is wasted on translation. You look at a 2D diagram of a heart in a textbook. Your brain has to:

- Decode the image.

- Mentally rotate it into 3D.

- Imagine how the blood flows through it.

- Remember the Latin names of the valves.

Steps 1 through 3 are "extraneous cognitive load." They are mental chores that don't actually help you understand the heart; they are just the tax you pay for using a 2D medium.

Removing the Tax

The study by Küçük et al. (2016) on learning anatomy via mobile Augmented Reality is a perfect illustration of what happens when you remove that tax. When students could view anatomical structures in AR—manipulating them, walking around them, seeing the spatial relationships directly—their achievement scores went up. Why? Because the brain stopped wasting energy on *visualizing* and started spending energy on *understanding*.

Thees et al. (2020) found similar results in university physics labs. Physics is notoriously abstract. AR bridges the gap between the invisible forces (vectors, fields) and the visible equipment.

**The implication here is profound:** We have been teaching with one hand tied behind our backs for centuries. We have been forcing students to run a "rendering engine" in their heads to convert text and diagrams into concepts. XR offloads that rendering to the GPU, freeing up the brain to actually think.

But before we get too excited about this educational utopia, we have to talk about the vomit.

Part 3: The Vestibular Tax (or, Why We Still Need Buckets)

I promised to be honest about the limitations. And this week’s research makes it clear: **Simulator Sickness (SS)** is still the bouncer at the club door, refusing to let a lot of people in.

We saw papers like Bimberg et al. (2020) discussing the "Simulator Sickness Questionnaire" (SSQ) and Vovk et al. (2018) specifically looking at sickness in AR with devices like the HoloLens.

The Sensory Conflict

Here is the mechanism: Your eyes tell your brain, "We are moving at 60 miles per hour through a virtual tunnel." Your vestibular system (the delicate fluid-filled loops in your inner ear) tells your brain, "We are sitting motionless in an office chair."

Your brain, evolving as it did over millions of years where the only reason for such a mismatch was usually *poisoning*, decides the safest course of action is to empty the contents of your stomach.

What’s concerning is that this isn't just a VR problem. Vovk et al. found it in AR training too. Even when you can see the real world around you, the overlay of digital objects moving unnaturally can trigger this response.

Why This Matters Now

This is the friction point for everything we just discussed.

- You want that deep social connection? Hard to feel "co-present" when you're nauseous.

- You want that reduced cognitive load in anatomy class? Well, if the AR headset makes you dizzy, your cognitive load just spiked through the roof trying to manage your own biology.

This isn't just a "get better screens" problem. It's a fundamental biological interface problem. Until we solve latency and sensory mismatch completely, XR will struggle to go truly mainstream for long-duration tasks. And "solving latency" isn't just about the headset—it's about the network.

Which leads us to the plumbing.

Part 4: The Nervous System of the World

This is the part of the research that usually gets glossed over because it’s dense and acronym-heavy. But if you're a nerd like me, this is where the magic is.

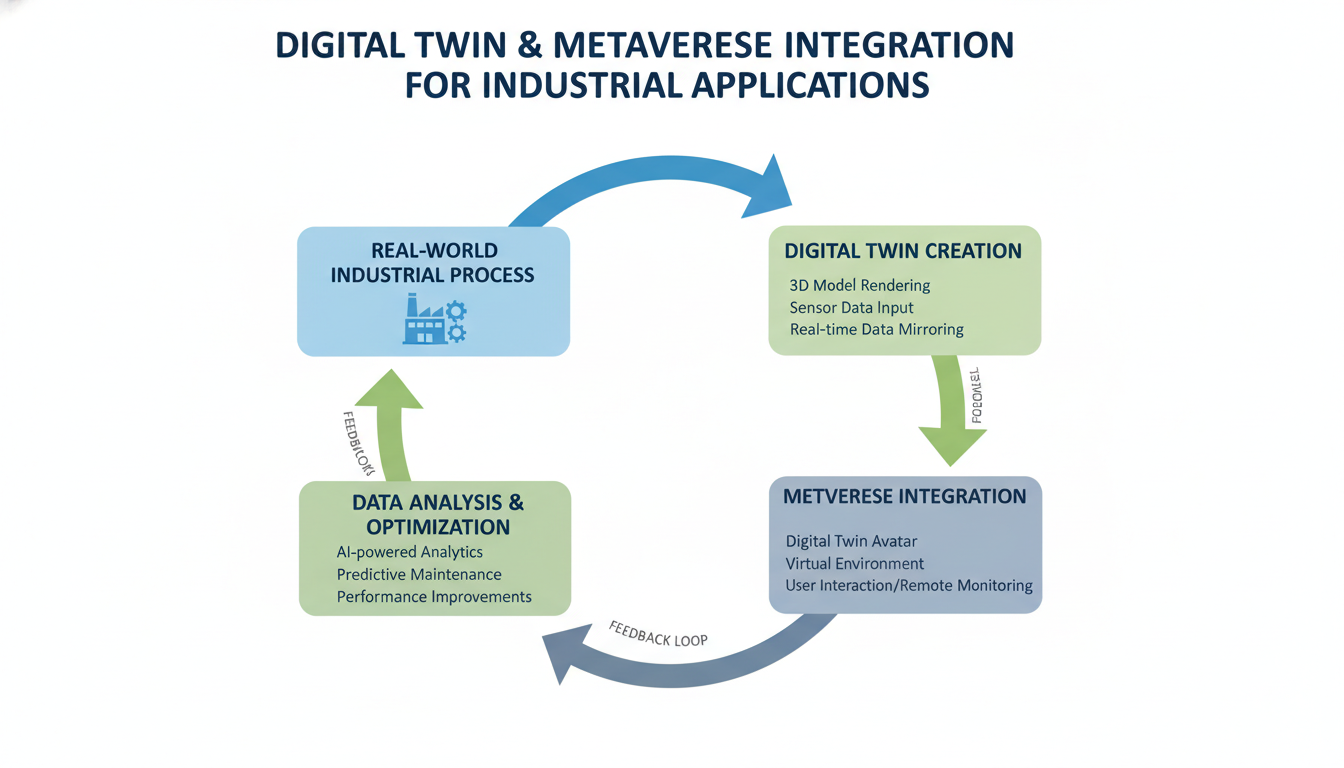

We are seeing a massive trend in the literature towards **Digital Twins** integrated with the Metaverse, supported by **Edge Intelligence** and **6G**.

The Digital Twin / Metaverse Convergence

Papers by Aloqaily et al. (2022) and Khan et al. (2022) are painting a picture of the Metaverse that is radically different from the "Ready Player One" fantasy. They aren't talking about a separate virtual world. They are talking about a real-time, high-fidelity digital mirror of *our* world.

Imagine a factory.

- **The Old Way:** A manager looks at a spreadsheet of production numbers.

- **The Digital Twin Way:** The manager puts on a headset (or looks at a screen) and sees a perfect 3D replica of the factory floor. Machines that are overheating are glowing red. Production lines are moving in real-time.

- **The Metaverse Way:** The manager, an engineer from Germany, and a safety inspector from Brazil all meet *inside* that Digital Twin. They walk around the virtual machine, discuss the glowing red part, and simulate a repair before anyone touches the real wrench.

The Infrastructure Crisis

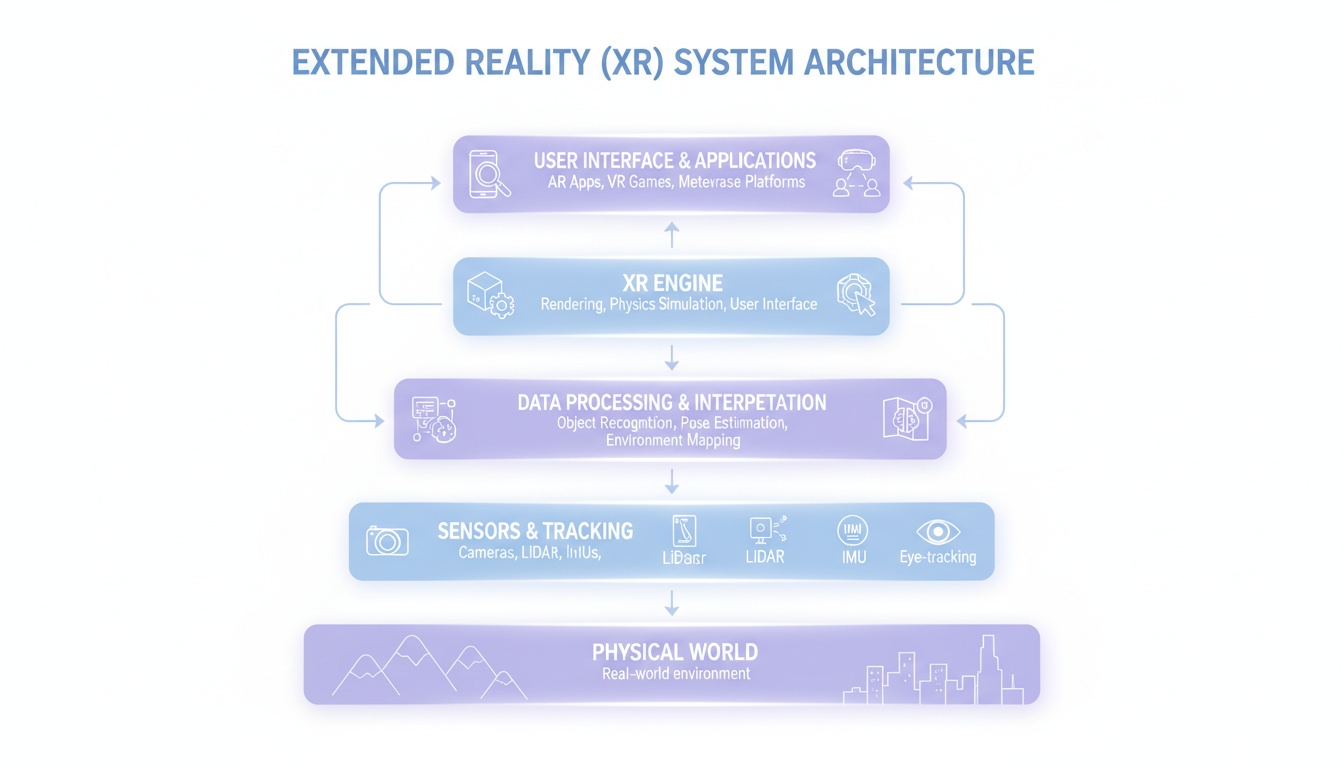

This sounds great, but the bandwidth requirements are astronomical. Huynh et al. (2022) discuss "Edge Intelligence-Based Ultra-Reliable and Low-Latency Communications."

Let’s break that down.

To make that Digital Twin work, you can't send data from the factory to a cloud server halfway across the world and back. The speed of light is too slow. If the engineer turns their head and the world lags by 50 milliseconds, they get sick (see Part 3).

So, we need **Edge Intelligence**—AI processing living right there in the factory, or on the cell tower down the street. And we need **6G** (as Khan et al. suggest) to handle the sheer volume of data.

Bhattacharya et al. (2023) go as far as to position the Metaverse as a key component of the "Future Internet."

**Speculating a bit here:** We are moving toward a world where the physical and digital are so tightly coupled that "going online" won't mean looking at a screen. It will mean engaging with the information layer that sits on top of reality. But we literally cannot build this yet. The network pipes aren't big enough. The research suggests we are in the "dial-up" era of the Metaverse.

Part 5: The Identity Crisis

Finally, we have to talk about who we are in this machine.

Wu & Wenxiang (2023) and Wang & Wang (2023) brought up the necessary legal and security frameworks.

If we are moving toward a world of Digital Twins and deep social presence, **Digital Identity** becomes the most valuable asset you own.

In the web 2.0 world, if your identity is stolen, someone buys stuff on your credit card. Bad, but fixable. In the Metaverse/XR world, your identity includes your biometric data—how you move, your eye gaze, your voice, your height.

Furthermore, as we spend more time in these spaces, the line between "avatar" and "self" blurs. The research into legal safeguards is currently playing catch-up to the technology. We are building the city before we've written the laws.

The Horizon: Where Do We Go From Here?

So, let’s synthesize this.

Based on the research from this week (and looking back at the trends from earlier this month), the narrative of XR has shifted.

- **It’s not an escape.** It’s a layer of utility and connection over the real world.

- **It’s an educational superpower.** By hacking our cognitive load, it makes us smarter, faster.

- **It’s a biological challenge.** Our bodies are resisting the simulation. The hardware needs to get better, or we need to evolve (I'm betting on the hardware).

- **It’s an infrastructure project.** Forget the headsets for a second; the real war is being fought over 6G and Edge computing to make the Digital Twins run.

We are in a fascinating, messy middle ground. We have the vision (connected, enhanced reality), we have the prototypes (AR anatomy apps, Digital Twin factories), but we are waiting for the infrastructure and the interface to catch up.

It reminds me a bit of the early days of the web. We knew it was going to change everything, but we were still waiting for the modem to screech its way to a connection.

For now, I’m excited about the potential to learn faster and connect deeper. But I’m keeping a bucket next to my desk, just in case.

Until next time,

**Fumi**

Source Research Report

This article is based on Fumi's research into Last Week's Research: Extended Reality. You can read the full research report for more details, citations, and sources.

📥 Download Research Report (Markdown)