The Algorithmic Composer: How AI is Learning the Language of Music

🎧 Listen to this article

Prefer audio? Listen to Fumi read this article (12:58)

If you’ve spent any time on the internet lately, you’ve probably heard—or *think* you’ve heard—AI-generated music. Maybe it was a lo-fi beat that sounded suspiciously generic, or perhaps a vocal clone of a famous rapper appearing on a track they never recorded. It’s easy to look at these viral moments and think, “Wow, computers are getting creative.”

But as someone who spends her evenings reading technical documentation (don’t judge), I can tell you that “creative” is a loaded word.

What’s actually happening under the hood is a fascinating collision of mathematics, signal processing, and linguistics. We are witnessing a quiet revolution in how machines understand sound. We’ve moved past the days of rigid, rule-based systems that sounded like a calculator trying to play Mozart. We are now in the era of Deep Learning, where models aren't just memorizing notes; they are trying to learn the *grammar* of music itself.

I’ve been digging through a stack of recent research papers—99 of them, to be precise—covering everything from Symbolic generation to raw audio synthesis. The findings are messy, exciting, and occasionally a little bit eerie.

So, grab your headphones. We’re going to look at how we got here, how the tech actually works, and why teaching a computer to hold a tune is infinitely harder than teaching it to write a poem.

Part I: The Two Languages of Music

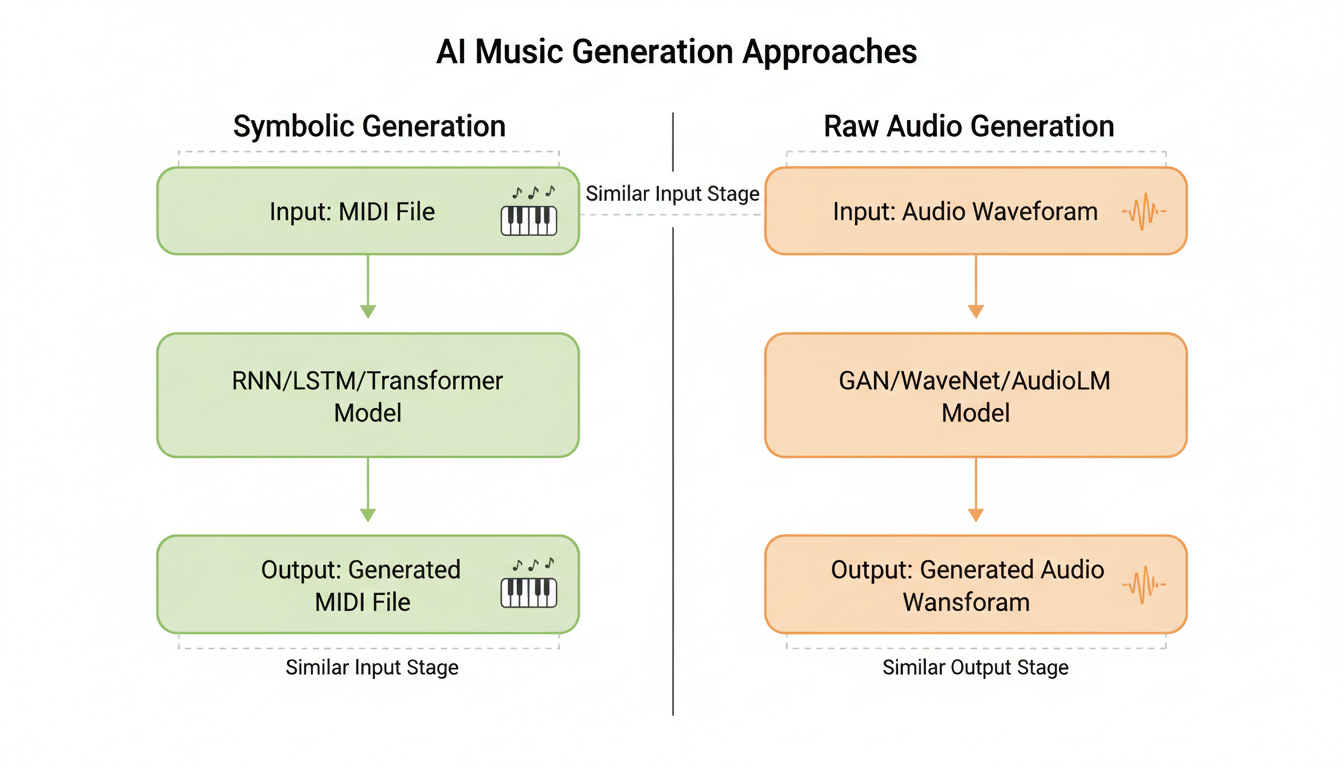

To understand where the research is today, we have to start with a fundamental divide in the field. When computer scientists try to generate music, they generally have to choose between two distinct “languages”: **Symbolic Representation** and **Raw Audio**.

Think of it this way: **Symbolic representation** is like sheet music. It tells you *what* to play—a C-sharp, quarter note, loud volume. **Raw audio** is the actual sound wave—the recording itself.

The Sheet Music Approach (Symbolic Generation)

For a long time, and indeed in much of the current research, Symbolic generation has been the king. This usually involves MIDI (Musical Instrument Digital Interface). If you’ve ever messed around with GarageBand, you know MIDI. It’s a set of instructions: "Press this key, at this time, with this much force."

According to a comprehensive survey by **Ji, Yang, and Luo (2023)**, symbolic generation remains a massive focus because it’s computationally efficient. A MIDI file is tiny. You’re manipulating discrete tokens—notes—which makes it very similar to text generation. If you think of a melody as a sentence and a note as a word, you can see why researchers love this. It allows them to borrow heavy-hitting techniques from Natural Language Processing (NLP).

However, there’s a catch. And it’s a big one.

> **The “Soul” Problem:** Symbolic music, by definition, lacks timbre. A MIDI file of a saxophone solo doesn’t sound like a saxophone; it sounds like a synthesizer *pretending* to be a saxophone. It lacks the breath, the squeak of the reed, the room tone—the stuff that makes music feel "real."

The Recording Approach (Raw Audio)

This is where the new wave of research is getting exciting. We are seeing a shift toward generating **Raw Audio** directly. Instead of predicting "C-sharp," the AI predicts the actual waveform—the fluctuating air pressure that hits your eardrum.

This is infinitely harder. A standard CD quality audio file has 44,100 samples *per second*. To generate a three-minute song, the model has to predict millions of data points, all in perfect sequence. If it messes up even a little, it doesn't just sound like a "wrong note"; it sounds like static or screeching feedback.

Despite the difficulty, recent breakthroughs like **AudioLM**, detailed by **Borsos et al. (2023)**, are proving that treating audio waveforms like language is possible (more on this later). This approach promises music that includes the texture, the production quality, and the nuance of a real recording.

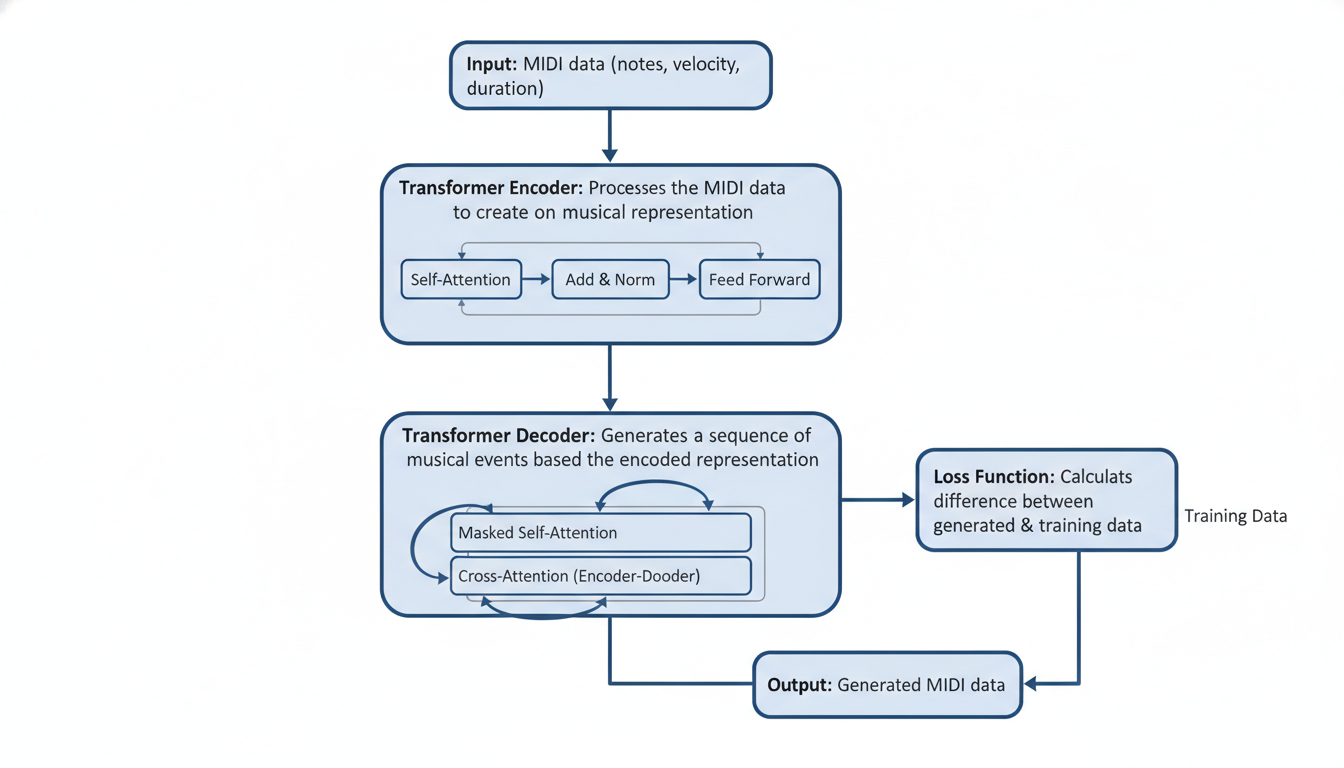

Part II: The Transformer Takeover

If you’ve followed AI at all, you’ve heard of **Transformers**. They are the architecture behind ChatGPT and essentially every major text model today. It turns out, they are also the rockstars of the music world.

The Memory of a Machine

Here’s the problem with older music AI (like Recurrent Neural Networks or RNNs): they had terrible short-term memory. An RNN might write a great melody for two bars, but by bar eight, it has completely forgotten what key it started in or what the main theme was. It’s like listening to someone noodle on a guitar while watching TV—it’s pleasant, but it’s not going anywhere.

Transformers changed the game because of a mechanism called **Self-Attention**.

Imagine you’re reading a mystery novel. When you read the word "killer" on page 200, your brain instantly links it back to the character introduced on page 5. You are maintaining a *long-range dependency*.

Music is full of these dependencies. A theme introduced in the intro might return in the bridge. A rhythmic motif in the drums needs to lock in with the bassline.

**Huang et al. (2018)** published the seminal paper on the **Music Transformer**, demonstrating that this architecture could handle these long-range musical structures better than anything before it. By using relative attention, the model could understand that a note wasn't just "Note #500," but rather "a note related to that other note from 10 seconds ago."

The Pop Music Specialist

Let’s look at a specific example of this in action. **Huang and Yang (2020)** developed the **Pop Music Transformer**.

They realized that pop music isn’t just a stream of notes; it’s highly structured around beats and bars. They modified the Transformer to explicitly model this beat-based structure.

**How it works:**

- **Event Tokens:** They represent music as a series of events (Note-On, Note-Off, Velocity shift, Time-Shift).

- **Beat Awareness:** The model is trained to recognize the rhythmic grid inherent in pop music.

- **Expressiveness:** It doesn't just output flat notes; it controls velocity (loudness) to mimic a human pianist's touch.

The result? Expressive pop piano compositions that actually sound like they have a verse, a chorus, and a sense of rhythmic groove. It’s a massive leap from the robotic, metronomic output of earlier models.

Part III: When Sound Becomes Language (The AudioLM Breakthrough)

I want to double-click on **AudioLM** (**Borsos et al., 2023**) because it represents a paradigm shift that blows my mind a little bit.

For years, the holy grail has been: *Can we just model sound the way we model text?*

If you ask GPT-4 to write a sentence, it predicts the next word based on probability. AudioLM asks: *Can we predict the next split-second of sound based on probability?*

The answer is yes, but you can't just feed raw waveforms into a Transformer—the data is too dense. The researchers at Google (Borsos et al.) figured out a clever workaround involving a hierarchy of tokens.

The Semantic vs. Acoustic Split

They realized that audio carries two types of information:

- **Semantic Information:** The "meaning" or structure (e.g., the melody, the phonemes in speech, the chord progression).

- **Acoustic Information:** The details (e.g., the timbre of the voice, the recording quality, the background noise).

AudioLM separates these.

- First, it uses a model (w2v-BERT) to map the audio to **Semantic Tokens**. This captures the "composition."

- Then, it uses a codec (SoundStream) to map the audio to **Acoustic Tokens**. This captures the "sound."

**The Process:**

- The AI generates the "Semantic" structure first (writing the song).

- Then, it uses that structure to generate the "Acoustic" details (performing/producing the song).

This "coarse-to-fine" generation allows the model to stay coherent over time (because of the semantic tokens) while sounding high-fidelity (because of the acoustic tokens). It’s like an architect drawing a blueprint before the bricklayers start working, rather than just laying bricks randomly and hoping a house appears.

Part IV: The Critics and The Optimizers (GANs and Genetic Algos)

Transformers aren't the only game in town. The research shows a vibrant ecosystem of other approaches, specifically **Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs)** and **Genetic Algorithms**.

The Forger and The Detective (GANs)

GANs are fascinating because they pit two neural networks against each other:

- **The Generator:** Tries to create a piece of music.

- **The Discriminator:** Tries to tell if the music is real (human-made) or fake (AI-made).

They are locked in an endless loop. The Generator gets better at lying; the Discriminator gets better at spotting the lie.

Research by **Muhamed et al. (2021)** explored **Transformer-GANs**. They combined the architectural strengths of Transformers with the adversarial training of GANs. Why? Because while Transformers are good at probability (predicting the next note), they can sometimes be "safe" and boring. GANs force the model to be more creative and realistic to fool the discriminator.

Similarly, **Cartagena Herrera (2021)** explored using Conditional GANs. This allows for control—you can tell the GAN, "Generate music, *but make it Jazz*." The discriminator then judges it not just on musicality, but on "Jazz-ness."

Survival of the Funkiest (Genetic Algorithms)

This is where the "nerd factor" goes off the charts. Some researchers are using **Genetic Algorithms (GAs)**—code inspired by biological evolution—to write music.

**Majidi and Toroghi (2022)** and **Dong (2023)** have published fascinating work on **Hybrid Models** that combine Deep Learning with Genetic Algorithms.

**How it works:**

- **Population:** The AI creates a bunch of random melodies or harmonies.

- **Fitness Function:** A Deep Learning model scores them. (Does this sound good? Does it match the chord progression?)

- **Selection & Crossover:** The best melodies are kept. They are "mated"—splicing the first half of Melody A with the second half of Melody B.

- **Mutation:** Random changes are introduced (change a C to a C-sharp) to prevent stagnation.

**Why do this?** Deep learning is great at learning patterns, but sometimes it gets stuck in a rut. Genetic Algorithms are optimization machines. By combining them, researchers found they could optimize for specific things—like generating a harmony that is both mathematically consonant *and* interesting—better than deep learning could do alone.

Part V: The Human Element (Expressiveness and Control)

One of the most recurring themes in the 99 papers I reviewed is the quest for **Expressiveness**.

Music isn't just dots on a page. If a robot plays a piano concerto with perfect mathematical timing, it sounds awful. It sounds dead. Human musicians rush the tempo slightly during exciting parts; they play softer during sad parts. This is called **micro-timing** and **dynamics**.

The Velocity Problem

**Huang and Yang’s Pop Music Transformer** (mentioned earlier) tackled this by treating "Velocity" (loudness) as a distinct token. The model doesn't just learn "Play C4"; it learns "Play C4 *softly*."

**Xie and Li (2020)** took a different approach, framing "Symbolic Music Playing Techniques" as a tagging problem. They trained models to add articulation tags—like staccato (short/detached) or legato (smooth/connected)—to the music.

This is a crucial step toward **Human-AI Collaboration**. Musicians don't just want a button that says "Make Song." They want control. They want to say, "Take this melody I wrote, but play it like a nervous jazz pianist." The research is slowly moving toward these kinds of controllable interfaces, but we aren't quite there yet.

Part VI: The Holes in the Sheet Music (Limitations)

I always tell my readers: don't believe the hype without checking the limitations. And this field has plenty.

1. The "Noodle" Factor (Long-Term Structure)

Despite the Transformer revolution, **Ji, Yang, and Luo (2023)** note in their survey that long-term musical coherence is still a massive challenge.

AI is great at the next 10 seconds. It’s okay at the next minute. But ask it to write a 5-minute song with an Intro, Verse, Chorus, Bridge, Solo, and Outro, and it often struggles. It tends to wander. It might start in a major key and drift into atonality without realizing it. It lacks a "holistic" view of the artwork. It’s writing word-by-word, not chapter-by-chapter.

2. The Black Box

For composers, these models are often frustrating "black boxes." You feed an input, you get an output. If you don't like it, you can't easily pop the hood and say, "adjust the bridge to be more syncopated." You just have to roll the dice again. Future research needs to focus on **interpretability** and **controllability**.

3. Evaluation is a Nightmare

How do you grade a song? In Image AI, we can measure pixel accuracy. In Text AI, we have benchmarks for grammar. But music?

Most papers rely on two things:

- **Objective Metrics:** Pitch density, rhythm consistency (math stuff).

- **Subjective Listening Tests:** Literally asking humans, "Does this sound good?"

This is subjective and slow. As the survey by **Ji et al.** points out, we desperately need better, standardized metrics to judge if an AI is actually being creative or just copying its training data.

The Horizon: What Comes Next?

So, where is this going?

Based on the trajectory of these 99 sources, the arrow points toward **Multimodal Generation**. We are seeing the beginnings of models that can take a text description ("A sad violin solo in a rainy cyberpunk city") and generate the raw audio.

We are also seeing a move toward **Genre-Specific Intelligence**. Instead of one "God Model" that plays everything, we might see specialized models for Jazz, Pop, or Classical that understand the deep nuances of those specific traditions.

But the most interesting development, in my opinion, is the potential for **Hybrid Creativity**. The research suggests that AI isn't replacing the composer; it's becoming a hyper-advanced instrument.

Imagine a synthesizer that doesn't just make a sound when you press a key, but listens to your melody and suggests a counter-melody in real-time. Imagine a drum machine that evolves its rhythm based on how aggressively you play the guitar.

The technology is still messy. It’s still figuring out the difference between a coherent song and a random sequence of beautiful sounds. But as it learns the language of music—from the syntax of MIDI to the phonetics of raw audio—it’s inviting us to jam.

And honestly? I’m ready to see what we can create together.

Stay curious,

**Fumi**

Source Research Report

This article is based on Fumi's research into AI Music Generation. You can read the full research report for more details, citations, and sources.

📥 Download Research Report (Markdown)